In ancient China, an emperor would be served by both eunuchs and palace maids. However, the eunuchs played a much more significant role and earned greater trusted from the emperor.

Why is that?

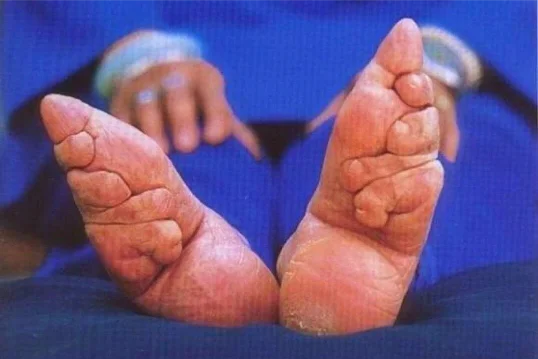

To state the obvious: eunuchs were castrated and could not have children.

Not having offspring was considered the most severe form of unfilial behavior. Therefore, eunuchs, being childless, were among the most looked down upon by society.

Not only were they physically disabled, but they were also “socially disabled” due to their lack of family ties. When a man became a eunuch, he was removed from the family genealogy; effectively disowned. Society heavily discriminated against eunuchs, leaving them with no meaningful relationships.

If a eunuch were to be abandoned by the emperor, they wouldn’t even be able to survive as a beggar outside the palace.

Eunuchs needed a powerful source of support to give them hope for a decent life, which only the emperor could provide. Backed by the emperor’s authority, eunuchs could disregard everyone outside the palace, and even the most powerful individuals had to bow before them.

All eunuchs aimed to become the emperor’s most trusted confidant. For the emperor, they posed no threat to his power and actually reinforced his control over the court.

From a security standpoint, those who served the emperor daily had to be his closest and most trustworthy aides; people who would never betray him. And who would never betray the emperor?

Even siblings can turn against each other, but someone who depends on you will not, because your interests are their interests.

Only eunuchs, who were both physically and socially disabled, eternally needed the emperor’s favor so would never betray him.

However, not all castrated men in the palace were called “eunuchs” (太监). This term referred specifically to high-ranking leaders and was not used for ordinary male servants. In the Ming and Qing dynasties, the highest-ranking eunuchs could achieve the fourth official rank and were generally classified as one of the “Three Outer Supervisors” or the “Twelve Inner Supervisors.”

Today, when we refer to eunuchs, we generally mean all male castrates in the palace.

While the eunuch system was large, most eunuchs in the palace performed manual labor. For example, the Supervisor of Meals managed food, the Supervisor of Clothing managed garments, and the Supervisor of Conduct organized the emperor’s outings.

However, some roles, like those in the Directorate of Ceremonial, were more specialized. The core members of the Directorate of Ceremonial were the Seal-Holding Eunuch, who held the emperor’s imperial seal, and the Pen-Holding Eunuch, who marked official documents on behalf of the emperor.

Eunuchs

Eunuchs promoted to the Directorate of Ceremonial were literate and had a certain level of cultural sophistication, something many palace maids lacked. The eunuchs in the Directorate of Ceremonial were no longer involved in manual labor; they had become part of the government’s decision-making framework.

If the emperor was hands-on, like Zhu Yuanzhang, who handled everything himself, the role of the Directorate of Ceremonial was limited to executing decisions.

However, if the emperor was more like Jiajing or Wanli, who rarely attended court, the Directorate of Ceremonial became extremely important.

The power of the eunuchs, represented by the Directorate of Ceremonial, and the power of the cabinet were in constant balance throughout the Ming Dynasty, shaping the government, society, and power struggles.

As mentioned earlier, diligent emperors had fewer problems with power-sharing, such as Zhu Yuanzhang, who reportedly reviewed 200–300 memorials (official reports) in a single day, and at his peak, processed 1,600. For perspective, you can visit a museum and try reading through a few to see if you can finish 20 in a day.

Memorials addressed every aspect of governance—personnel appointments, troop movements, river management, tax adjustments, etc., and required careful consideration. To review one memorial properly, the emperor needed a good grasp of the overall situation.

Even a hardworking emperor was overwhelmed by the workload. In one case, the Minister of Revenue, Ru Taisu, submitted a memorial over 10,000 words long. Zhu Yuanzhang became so frustrated after he had read half of it and it still didn’t get to the point, that he summoned the minister to the palace and had him beaten.

If a workaholic like Zhu Yuanzhang couldn’t handle the load, his descendants certainly couldn’t either. They needed the help of the bureaucratic system, effectively delegating some imperial power to the civil service, whose leader was the grand chancellor (or prime minister, depending on the era). When grand chancellors performed well, emperors became less essential. History records multiple instances where a grand chancellor even replaced the emperor.

To prevent this, Zhu Yuanzhang abolished the grand chancellor role altogether, which left him with no choice but to take on all the work himself.

By the time the throne passed to Zhu Yuanzhang’s grandson, the Jianwen Emperor, the burden became too much, so he established the Cabinet. The Jianwen Emperor, although hardworking, was not as familiar with court affairs as Zhu Yuanzhang, so he needed an advisory body to help him make decisions.

Although the Cabinet was limited in many ways—for example, its top rank was only fifth, and its role was advisory while the emperor made the final decisions—it gradually became the most powerful institution of the Ming civil service, with the Chief Grand Secretary functioning as a de facto prime minister.

The conclusions of this development were that a country needs stable governance, and ministerial power is indispensable. The emperor cannot handle everything, no matter how diligent he is.

Once ministerial power is established, it inevitably poses a threat to imperial power. Therefore, the Ming emperors chose to support the eunuchs to counterbalance the power of the ministers.

From the Xuande Emperor onward, the political workflow in the Ming Dynasty involved memorials from across the empire being initially reviewed by the Cabinet, which wrote recommendations on behalf of the emperor. These were then passed to the Directorate of Ceremonial for the emperor’s final instructions.

At first, the Directorate of Ceremonial merely carried out the emperor’s will. Later, they began making decisions themselves, and eventually, some emperors would only mark a few documents while leaving the bulk of the work to the eunuchs. By the mid-to-late Ming Dynasty, both ministerial and eunuch powers had carved out a portion of the imperial power, balancing each other.

At its height, eunuch power could rival the civil service, as seen during the reigns of Wang Zhen and Feng Bao.

At its extreme, as in the case of Liu Jin, eunuch power could dominate the civil service, with personnel appointments and decisions being dictated by Liu Jin, despite his status as a eunuch.

Strictly speaking, eunuch power was an extension of imperial power. The political systems of the Ming and Qing dynasties maintained sufficient control over eunuchs. Even when eunuchs like Liu Jin held immense power, the emperor could easily remove them without resistance. However, removing a grand chancellor with similar power would have been much more difficult. This is why emperors trusted eunuchs more—eunuch power often directly represented imperial power itself.

Thus, eunuchs in the palace were not merely servants; they became an integral part of the emperor’s control over the court and the entire political system. This was a role that palace maids could not replace.