There is an old saying in China: “The people consider food as their heaven,” which highlights the sacred role of sustenance in Chinese culture. This reverence runs so deep that in ancient mythology, there was even a god who was responsible for teaching people about fishing, hunting, and farming, solving the problem of providing food.

This shows how significant food itself, as well as the gods who provided it, held unparalleled spiritual weight in the hearts of ordinary people.

In Chinese culture, there is a tendency toward what we could call “pan-foodism,” where almost anything can be linked to food or has some connection to eating. For example, in Chinese, the word “ren” – “person” can also be referred to as “kou” (口), which means “mouth.” Together, they form the word “renkou” (人口), meaning population. If you look at these characters, you’ll notice that “ren” (人) resembles two legs, while “kou” (口) looks like an open mouth.

This linguistic playfulness extends to livelihood metaphors:

a profession or job is often called “rice bowls” (饭碗):

Shoemakers or repairing pots are described as “eating craft-rice” (吃手艺饭)”

Street performers are described as “eating talk-rice” (吃开口饭)

Teachers are described as “eat chalk dust” (吃粉笔灰)

and renting out houses is described as “eating roof tiles.”

Living off savings is described as “eating the old capital” (吃老本)

If they run out of savings and have no income, the situation is serious, and it can be described as “drinking the northwest wind”—a poetic nod to starving through winter gales.

You see that there are many figurative expressions that connect different professions to the act of eating.

And many of these expressions are direct translations from Chinese, but if we translate them literally into the most correct English, they lose their flavor and become harder to understand in context. To capture the true essence, we might need to rephrase them in a way that feels natural in both English and Chinese while maintaining the underlying message.

The most envied situation is “eating the emperor’s grain,” which refers to those who hold an “iron rice bowl.” This means they are assured a stable income, as the emperor’s grain represents an endless supply of food. If you became a government official, even if you were not rich, you would have no worries about food and clothing anymore, and you wouldn’t need to struggle for a living. After all, starting a business or entrepreneurship comes with risks and requires capital.

Even today, becoming a civil servant or government official is still considered the most stable career choice by many Chinese people. To help you better understand China’s current system, here’s a brief detour:

In China, the official retirement age is 58 for women and 63 for men. This means women can start receiving a state pension at 58, while men must work until 63 to qualify. Most Chinese citizens pay into social security (pension) and medical insurance monthly. In my city, the minimum combined contribution is around ¥1,700/month (~$234 USD). After contributing for at least 15 years, you become eligible for pension payments.

Of course, no one starts working at 20 just to retire at 35 for a pension. The longer you pay into the system, the higher your pension after retirement. Essentially, the healthier and longer you live, the more pension benefits you’ll receive.

For many young and middle-aged people, a key reason to pay into social security is medical insurance. With it, most or all costs for hospital visits, medications, surgeries, and hospital stays can be reimbursed.

For example:

My medical insurance allocates ¥2,000/year (~$275 USD) to my “pooled insurance fund.”

For small medical expenses (under ¥2,000), this fund covers the full amount.

For larger costs, an additional ¥13,000 (~$1,785 USD) from the medical insurance social pooling reimburses 70-90% of expenses, depending on the type of treatment or medication.

Medical Insurance Social Pooling – a risk-sharing mechanism where all participants’ premiums are pooled to cover major medical expenses.”

If you use up the initial ¥2,000, the higher-tier ¥13,000 kicks in. For instance, a ¥10,000 medication bill might leave you paying only ¥3,000 out-of-pocket after 70% reimbursement.

I’ll dive deeper into China’s social security formulas and specifics in future articles if there’s interest. Every country has its pros and cons—China included. It’s important to stay objective when comparing systems.

Now, after all this digression, let’s get back to the main topic.

In fact, there are many more expressions in Chinese that use the concept of “eating” metaphorically. For example, deep thinking is called “chewing over” (咀嚼), jealousy is “eating vinegar” (吃醋), something familiar and ordinary is “daily food” (家常便饭), and something easy to accomplish is “a small dish” (小菜一碟). These are just a few examples of how food-related words and rhetorical devices are deeply embedded in the Chinese language.

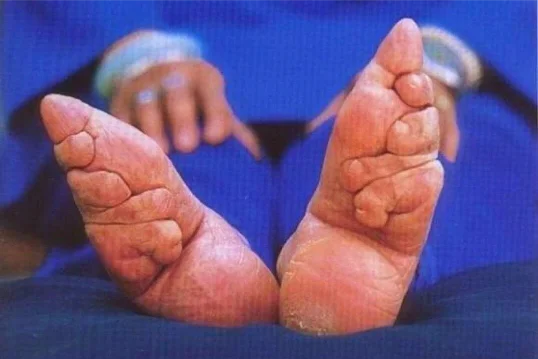

The reason why Chinese people treat eating as a top priority is largely because of historical struggles with hunger. The Chinese civilization is an agricultural society, and one of the major characteristics of agricultural communities is that people must wait for crops to mature before they have food to eat. From spring plowing to summer weeding and then to autumn harvest, the process is incredibly long. During this period, there was always the uncertainty of going hungry. And then there were years of natural disasters—how could every year be blessed with favorable weather? Floods, droughts, storms—there was no way to fully guard against them. Just when the wheat was ripening and ready for harvest, a sudden hailstorm could wipe out an entire season’s work, leaving nothing behind. Because of this constant fear of food shortages, agricultural societies developed a strong sense of insecurity, always worrying about the possibility of famine.

This is why eating became such a serious matter.

In China, eating is not just an important necessity, but also a fundamental right. In ancient China’s autocratic society, there was no real concept of human rights. A prime minister could be publicly flogged, and a county magistrate could whip commoners at will. Whether officials or ordinary people, they had neither freedom of thought nor speech, nor privacy or the right to information—but they all had the “right to eat.” Even criminals sentenced to death were given a full meal before execution, and relatives and friends were even allowed to bring food and wine to the execution ground. This practice was known as “not executing someone who is starving” (不杀饿死之人). (Many legendary heroes in Chinese history have used this tradition as an opportunity to stage prison rescues.)

In Chinese culture, the concept of a “hungry ghost” is one of the most pitiful fates. To deny a dying person their final meal was considered even crueler than killing them. Some regions in China still uphold the tradition of feeding wandering spirits during the annual Ghost Festival. On this day, the King of Hell is said to release lonely spirits to roam the world in search of food. Families prepare grand feasts and place offerings at their doorsteps for these “wild ghosts” to consume. This tradition stems from the deeply held Chinese belief that hungry ghosts are truly pitiful.

This isn’t surprising at all—after all, “The people regard food as their heaven.” Without food, not only is life unlivable, but even death offers no peace.

Food is no trivial matter; it cannot be taken lightly. If mishandled, it can lead to chaos and crisis. In Chinese history, times of great prosperity were marked by favorable weather, abundant harvests, and national stability. On the other hand, periods of turmoil and dynastic changes were often accompanied by natural disasters, endless famines, and widespread starvation, where people even resorted to eating human flesh to survive. In such desperate times, if someone were to open granaries and distribute food, the starving masses would immediately follow them without hesitation.

Thus, it can be said that in ancient China, the foremost political issue was always the issue of food. Any ruling power could only secure the people’s loyalty and rule the land by ensuring they had enough to eat. Gaining public support (“winning the people’s hearts”) was directly linked to the ability to provide food, and only after solving this issue could a government maintain stability.

In this sense, food was not just a necessity—it was a political matter.

Politics is Eating—A Common View Among Many Politicians

In the eyes of ancient Chinese politicians and thinkers, governing a country was much like preparing and cooking food. Laozi once said, “Governing a large country is like cooking a small fish.” The idea behind this metaphor is that when cooking small fish, one cannot stir and flip them excessively, or they will fall apart. Similarly, governing a country requires a careful, light-handed approach—ruling with stability rather than excessive interference. Constantly launching political movements or making drastic changes could only lead to chaos, social unrest, and suffering among the people.

This is not just a simple metaphor. In China, politics has often revolved around eating—or at least, discussing national affairs over meals. Hosting political discussions at banquets is a long-standing tradition. For example, the Rituals of Zhou mention a ceremony called “xiang yin jiu li” (乡饮酒礼), which was essentially a formal political consultation meeting disguised as a drinking banquet. According to this tradition, rulers, ministers, and local officials were expected to host gatherings (reportedly every three years) where they invited respected elders, capable leaders, and distinguished scholars to drink and discuss important state matters. Ancient Chinese society valued the wisdom of the elderly and the intelligence of the virtuous, so such meetings were both effective and necessary. However, the fact that these political meetings had to be held in the form of a drinking banquet—and were officially named “the rural drinking ceremony”—is certainly a uniquely Chinese characteristic.

Since politics and eating were so closely linked, one’s ability to eat, understanding of food, and skill in handling dining-related matters became indicators of their competence—not just in social settings, but in governance, military leadership, and even seizing power. There are historical examples of this principle in action.

Take, for instance, the famous general Lian Po of the Zhao state. To prove that he was still as strong as ever despite his age, he demonstrated his vitality by devouring an entire dou (about 10 liters) of rice and 10 pounds of meat in front of the king’s envoy. However, the envoy had been bribed by Lian Po’s political enemies. Upon returning to report to the Zhao king, the envoy remarked, “The old general still has a great appetite, but his digestion seems to be failing. During the meal, he went to relieve himself three times.”

Hearing this, the Zhao king hesitated. His hesitation ultimately led to Lian Po’s political downfall—his impressive meal turned out to be in vain.

This anecdote takes place during a time when Zhao faced strong external threats and lacked competent military leaders. The king considered reinstating Lian Po, who had once been a legendary general, but was unsure about his physical condition. He sent an envoy to assess whether Lian Po was still fit for command. The envoy’s report—though brief—was packed with implications: on one hand, it suggested that Lian Po was still eating heartily, a sign of retained strength; on the other hand, it hinted that his aging body might no longer be as resilient as before.

Thus, in ancient China, a ruler selecting his most trusted generals might even use their appetite as an indicator of their physical state. Observing a person’s eating habits as a way to assess their capabilities—this, too, was an art in itself.

If great generals like Lian Po were known for their ability to eat, then great prime ministers were often those who excelled at managing other people’s meals. Take Chen Ping, for example. In his youth, he served as a “zai” (宰) in his hometown. The “zai” was responsible for distributing “zuo rou” (胙肉)—the sacrificial meat used in rituals to honor the communal gods. Since the gods didn’t actually consume the offerings, after the ceremony, the meat would be distributed among the people so they could share in the divine blessings. This was not an easy job. If the meat was distributed unfairly, it could lead to disputes and turn a sacred occasion into a source of conflict.

However, despite his young age, Chen Ping handled the task exceptionally well, distributing the meat with remarkable fairness. The elders of the village praised him, saying, “This young man is truly skilled at being our ritual ‘zai’!” Chen Ping, full of confidence, boldly replied, “Ah! If I were to become the ‘zai’ of the whole country, then our state would be as well-organized as this portioned meat!”

And indeed, he later “carved up the nation” in a different way—becoming a founding statesman of the Western Han Dynasty and a wise prime minister.

While a “zai” at a communal festival was technically a butcher, they still played a role in religious affairs (even if only in an amateur capacity). However, the legendary prime minister Yi Yin of the Shang Dynasty may have actually been a cook before he rose to power. The historical records about his background are unclear, but he was undoubtedly of humble origins—perhaps a commoner or even a slave. Ancient texts such as Mozi, Lüshi Chunqiu, and Records of the Grand Historian mention that Yi Yin was a “yìng chén” (媵臣)—a servant sent as part of a bride’s dowry.

Most likely, his culinary skills were the reason he was chosen for this role. After entering the royal household, he became the head chef in the palace, not only managing daily meals but possibly also overseeing food offerings for rituals and sacrifices. His dishes must have been exceptionally good, as King Tang of Shang became deeply impressed. Yi Yin seized this opportunity to explain his philosophy to Tang, using cooking as a metaphor for governing a country. He argued that just as the best flavors require careful balance, so too does ruling a nation. He even coined the famous phrase, “Governing a large country is like cooking a small fish.”

King Tang was so impressed that he promoted Yi Yin to the position of right-hand minister (you xiang, 右相), making him one of the earliest and most renowned prime ministers in Chinese history. This story became known as “Yi Yin winning over Tang through cooking” (伊尹以割烹要汤) or “Persuading Tang with flavors while carrying pots and knives” (负鼎俎以滋味说汤).”

From the Warring States period onward, scholars have debated the historical accuracy of this account. Mencius even outright denied it. Whether Yi Yin was truly a cook before becoming prime minister remains uncertain. However, in ancient times, it was entirely possible for a cook to rise to the rank of prime minister.

After all, what is a Zai Xiang (prime minister)? The character “zai” (宰) means to slaughter sacrificial animals and portion meat, while “xiang” (相) refers to conducting ceremonies and serving guests. In essence, a prime minister was a combination of a master chef and a ceremonial host. The “zai” handled the butchering and food preparation, while the “xiang” oversaw the banquet and entertained nobles. Together, they formed the role of prime minister. Of course, since they were responsible for distributing sacrificial meat to the nation’s highest-ranking officials, this role could only be entrusted to an elite scholar.

A government led by such individuals might as well be called a “kitchen cabinet.”

It is truly unique to Chinese history—placing the government’s headquarters in the kitchen and appointing a chef as prime minister.

Yet, this is hardly surprising. If the emperor rules the country as though it were his household, then household affairs are equivalent to state affairs. And if “the people regard food as their heaven,” then governing the people is essentially the same as managing food.

Besides, how could any political leader remain ignorant of kitchen affairs when banquets were such an integral part of political life?

- Offerings to gods, spirits, and ancestors required feasts.

- Hosting foreign dignitaries and signing treaties required feasts.

- Rewarding ministers and discussing state matters required feasts.

- Even summoning elders for political consultation meetings required feasts.

Given all this, how could a prime minister—the nation’s ‘chief steward’—not understand food and banquets?

Governing a Nation Is Essentially Distributing Food

Since “the people regard food as their heaven,” governing a country can, in a broad sense, be seen as managing the distribution of food. This is why Chen Ping’s ability to distribute sacrificial meat “with great fairness” proved that he was capable of becoming “the grand steward of the entire nation” (天下之宰).

Food distribution involves three key aspects:

- Quantity – how much one receives.

- Quality – the grade or excellence of the food.

- Order – who gets to eat first and who must wait.

The general rule is that the higher one’s status, the more, better, and sooner they eat, while those of lower status receive less, worse, and later portions. For instance, the ancient food-serving trays (called “dou” in antiquity) were not equal for everyone. The emperor was entitled to twenty-six trays, dukes had sixteen, marquises had twelve, high-ranking officials had eight, and lower-ranking officials had six. This was the standard of “fairness” (均). If you think fairness means everyone gets the same, then that would be a grave mistake.

Clearly, distributing food was no easy task. To prevent chaos, everything had to be carefully arranged in advance—starting with seating arrangements.

In ancient times, people sat on mats on the floor, which is why one’s seat (席, xí) referred both to physical seating and social status. The most important figures—rulers, central figures, or honored guests—were seated at the main seat (主席, zhǔxí), while others were seated in rows based on hierarchy (列席). Who gets to sit where was strictly determined by etiquette (礼, lǐ).

Beyond seating, drinking vessels were also symbols of status. There were two key vessels:

Zun

- Zun (尊) – a wine container placed before the highest-ranking individual. This is why the word “zun” (尊) later came to mean “reverence” or “honor”.

- Jue (爵) – a wine cup, which everyone had, but of varying materials based on rank. Ministers drank from jade cups, high officials from fine stone cups, and lower officials from scattered common cups. This association between 爵 (wine cup) and 爵位 (noble rank) directly linked drinking to status, making the term “rank” (爵位, juéwèi) synonymous with a noble title.

Jue

With such elaborate distinctions surrounding a simple drinking vessel, one can only imagine the political significance of food itself.

Power Over the Cauldron Is Power Over the State

A grand banquet could never consist of wine alone—it had to be accompanied by meat. Wine was kept in zun, while meat was cooked in ding (鼎), large bronze cooking vessels. These came in two forms:

Round Ding

- Round, three-legged cauldrons with two handles.

- Square, four-legged cauldrons for larger feasts.

Square Ding

Some massive ding could cook entire cows or sheep, while smaller ones were used for stewing chickens and fish. The larger the cauldron, the grander the spectacle. However, more cauldrons also meant greater prestige.

According to Zhou dynasty protocol, feudal lords were entitled to five ding, each used to prepare different meats:

- Beef

- Lamb

- Pork

- Fish

- Wild game (e.g., deer)

This tradition was called “列鼎而食” (“feasting in rows of cauldrons”).

During feasts, as drums and bells sounded, the banquet host—often the prime minister—would follow the rituals (礼) or the monarch’s instructions. Using a ceremonial knife (匕, bǐ), they would carve meat from the ding and distribute it onto individual food trays (俎, zǔ). The higher one’s rank, the better the cut of meat received. This entire ritual was called “钟鸣鼎食” (“Feasting with bells and cauldrons ringing”).

Clearly, who controlled the cauldron controlled the distribution of food—and if one controlled the national cauldron, they controlled political power.

This is why, when Yu the Great became leader of the tribal alliance that unified China, one of his first major acts was to cast the Nine Cauldrons (铸九鼎). The bronze used for these cauldrons supposedly came from the nine regions of China (九州), symbolizing control over all the food and resources of the land.

For centuries, these Nine Cauldrons remained the ultimate symbol of sovereignty. During the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties, they were regarded as the national treasure of the state.

- When the Shang dynasty overthrew the Xia, King Tang seized the cauldrons and moved them to his capital.

- When the Zhou defeated the Shang, King Wu relocated the cauldrons to his new royal city.

Wherever the ding were placed, the seat of power followed. The cauldrons were the embodiment of political legitimacy.

In 606 BCE, the King of Chu led an army to intimidate the weakened Zhou dynasty and conducted military drills near the Luo River. To assert his dominance, he sent an envoy to the Zhou court, asking, “How large and heavy are the Nine Cauldrons?”

This was not just an innocent inquiry about kitchenware—it was a direct challenge to the Zhou throne, signaling an ambition to seize power.

This event became known as “Wen Ding” (问鼎, “Questioning the Cauldrons”), an idiom that now means coveting political power. Conversely, “Ding Ding” (定鼎, “Setting the Cauldrons”) means establishing a new regime.

From Kitchen Politics to National Governance

Wherever the cauldron of governance was placed, the center of power followed. Ministers and nobles had no choice but to revolve around it. This is why:

- The position of prime minister was referred to as “Ding Nai” (鼎鼐).

- Key government officials were called “Ding Chen” (鼎臣).

- The three highest-ranking ministers were called “Ding Fu” (鼎辅).

- A dynasty’s legitimacy was called “Ding Zuo” (鼎祚).

- A nation in its golden age was described as “Ding Sheng” (鼎盛).

- When three forces stood in balance, it was called “Ding Li” (鼎立).

Without understanding China’s deep cultural link between politics and food, it is impossible to grasp how a bronze pot for stewing beef could hold such immense significance in political history.

The Prime Minister as the Nation’s Head Chef

In ancient China, the prime minister (宰相) was essentially a head steward, managing not just politics but also the nation’s food supply.

In the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties, the highest-ranking minister—called “Tian Guan Zhong Zai” (天官冢宰)—was often the chief supervisor of the royal kitchen. Over 60% of his bureaucratic staff were in the food department, including:

- 152 royal chefs (膳夫) for the palace.

- 128 banquet managers (内饔) for private royal feasts.

- 128 external banquet managers (外饔) for state ceremonies.

- 70 kitchen supervisors (庖人) overseeing all meals.

- 62 butchers (亨人) preparing meat.

- 335 gamekeepers (甸师) providing wild meat.

- 342 fish suppliers (渔人) catching seafood.

- 340 brewers (酒人) producing wine.

With such a vast culinary bureaucracy, calling the prime minister the “head of general affairs”—or even “the executive chef”—was not an exaggeration.