The Great Wall, aside from its military defense function, had another critical yet often forgotten role.

It’s well known that the Great Wall served as a defense structure to block the cavalry of nomadic tribes from the north.

However, when we climb the steep ridges of this wild wall, marveling at the grandeur of ancient Chinese ingenuity, a question inevitably arises:

Was it really necessary to build additional walls on top of these mountains, which are hundreds of meters high and already steep enough to block troops and war horses?

The wall itself isn’t that tall – it’s the mountains that provide the real height. But the higher and steeper the mountains are, surely the less need there is to build a wall on top of them?

What we see here is the Great Wall atop towering mountains. Horses would already struggle to cross these mountain ridges, reducing the mobility and offensive advantage a cavalry has. A beacon tower for early warning would suffice, so why go to the extra effort of building endless walls?

Thinner walls are found in deserts and grasslands, like the ones shown below. How could these walls resist the full-scale attacks of nomadic armies?

Take the vast Gobi Desert for example. Could a nomadic army not just break a small section of the wall in a less-guarded area to let their troops pass through?

Indeed, historical records show numerous instances where nomadic tribes “broke through the border walls” to invade.

Some people argue that soldiers could be deployed along the Great Wall to enhance the mobility of the infantry.

But with these thinner walls, how could soldiers be deployed? Even if the walls were wider in ancient times, allowing for troop movements, most beacon towers were solid without any passageways through. So how would deploying troops increase mobility?

One of the most well-known parts of the Great Wall is the Badaling section, where troops could indeed be deployed. The walls here are wide enough, and the watchtowers have doors on both sides for passage.

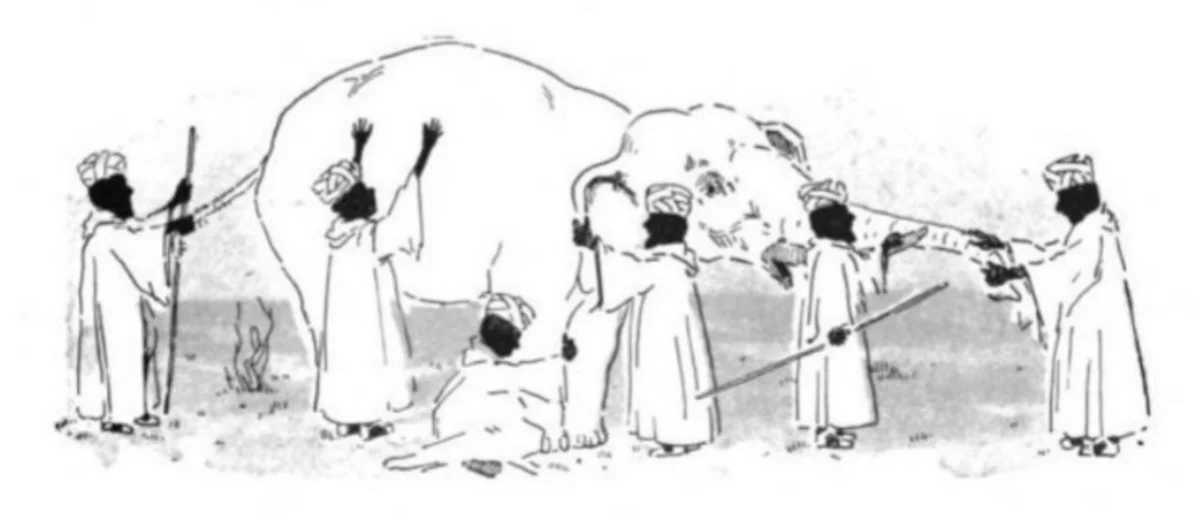

This has led to a cognitive bias, making people believe that all sections of the Great Wall are built this way. But that’s not the case. It’s like the story of the blind men and the elephant, one person touches the tail and concludes the elephant is like a rope. While his conclusion isn’t wrong, it is incomplete.

These higher-quality walls only cover a few hundred kilometers, a small fraction of the thousands of kilometers built. In most cases, the walls resembled the picture below: solid beacon towers without windows or doors and no way for deploying troops to pass through.

The hollow, brick-covered watchtowers like the ones at Badaling didn’t appear until the Ming Dynasty. For more than 2,000 years prior, the vast majority of the walls were made of rammed earth, with very few hollow, brick-covered towers. Thus, most of the Great Wall didn’t have the function to deploy troops.

Interestingly, nomadic regimes also built their own walls. For example, the Khitans built a wall in the Mongolian grasslands north of the Gobi Desert, and other fortifications can be found alongside the Yenisei River in Russia’s Tuva region. Of course, the walls built by nomads were typically lower and only a few hundred kilometers long, often lacking beacon towers and fortresses.

But why did the nomads build walls too?

By now, you might have realized that the Great Wall didn’t need to be very tall, nor was it necessary for transporting troops. Even simple rammed-earth walls or short, modest walls had a purpose. There must have been a reason why the ancients built them.

Building the Great Wall reduced uncertainty from a military perspective

In the era of cold weapons, cavalries had a significant advantage over infantries. Cavalries were faster, had a stronger impact, and their archery could strike from greater distances.

To counteract this, various systems and strategies were employed, such as shields, barricades, wagon formations, and units armed with long spears.

History offers many examples of infantry legions defeating cavalries. However, these tactics rely on one crucial condition: they only work on the battlefield, where forces are concentrated, and movement is limited. Outside the battlefield, in a broader spatial context, a cavalry’s mobility renders these methods ineffective.

Due to a cavalry’s speed, they could concentrate their forces locally, forming a numerical advantage over infantries and defeating them one by one. You can search for Lanchester’s Law to learn more about this.

Another significant advantage cavalries had was their mobility. Mobility means flexibility, and that introduces uncertainty:

- You don’t know when cavalries will attack. They could suddenly appear in broad daylight or launch a stealthy night raid. This creates temporal uncertainty.

- You don’t know from which direction a cavalry will come, where they will strike next, or where you should go to chase them. This creates spatial uncertainty.

- You don’t know how many cavalry units there will be. It could be a small group of dozens or hundreds, or it could be a large-scale assault involving tens of thousands. Different enemy sizes require entirely different strategies, yet it’s difficult to gauge their numbers and formulate a response. This creates numerical uncertainty.

The secrecy of these three critical pieces of information – time, location, and size – gave cavalries a nearly insurmountable advantage: uncertainty.

Cavalries moved like the wind, gathering and dispersing unpredictably. Even a small group could suddenly raid without warning. During an attack, they could combine forces to achieve local superiority, then quickly disperse upon retreat, luring pursuers into dangerous situations and launching counterattacks at will.

Defenders, meanwhile, couldn’t muster their forces quickly enough and could only respond passively. After a raid, cavalries would swiftly retreat and relocate. By the time the defenders gathered troops for pursuit, they would find the enemy had long since fled, with no clue where to chase. Even if they managed to intercept part of the force, they could only catch a small fraction, making it difficult to coordinate with nearby forces to surround and annihilate the enemy.

This kind of fragmented raiding and harassment would make border villages chaotic and insecure. If borderlands were continually subjected to raids, no one would be willing to stay there.

How could we reduce the uncertainty caused by cavalries?

This is where beacon towers come into play, helping to compensate for the lack of information and reduce the uncertainty that cavalries posed.

- Speed of information: The speed at which beacon signals are relayed far exceeds that of cavalries. This gives those in the rear an early warning, allowing them to estimate the arrival time of the enemy and prepare in advance for the attack. This reduces temporal uncertainty.

- Direction and order of the signals: By observing the direction and the sequence in which the beacon fires are lit, defenders can determine the approximate direction and distance of the incoming enemy. This helps reduce spatial uncertainty.

- Estimating enemy numbers: The shape of the beacon fire, along with the number of hanging lamps or flags displayed from the beacon tower, can provide an estimate of the enemy’s size, helping defenders plan their response. This reduces numerical uncertainty.

The Wujing Zongyao (Complete Essentials for the Military Classics) from the Northern Song Dynasty, describes beacon fires:

“In a single day and night, the signal can be transmitted over 2,000 li (approximately 1,000 kilometers).”

This speed far exceeds that of a cavalry. When faced with a large-scale cavalry invasion, beacon towers give sufficient time to prepare and gather forces.

As for determining the enemy’s position, this can be done by constructing beacon towers in various directions around a fortified town.

To gauge the enemy’s numbers, different signals could be encoded to reflect the size of the invading force. For example, the Tang Liudian (The six statutes of the Tang Dynasty) states:

“One torch, two torches, three torches, four torches – varying based on the size of the enemy force.”

With this system, the defenders would have essential information on the enemy’s timing, location, and numbers, allowing them to formulate defensive or offensive strategies. This information was invaluable because without sufficient data, decisions carried significant risks. History offers countless examples of armies being lured into rash decisions, like launching an attack before reinforcements arrived, only to be ambushed and wiped out.

Even with ample forces, intercepting and encircling enemy cavalries required more than just beacon towers. The amount of information beacon towers could transmit was still limited. While sufficient for defensive preparations, it wasn’t enough for more complex operations like interception or encirclement.

To solve this problem, our main character – the Great Wall – finally comes into play. The seemingly small and thin sections of the wall, often dismissed by many, were also effective in reducing the uncertainty cavalries brought and played a crucial role in eliminating invaders.

What was the purpose of the Great Wall?

The primary role of the Great Wall was to intercept and delay invasion from cavalries.

First, it’s important to clarify that no wall could completely block a large-scale military invasion. The ancients never expected these relatively low walls to stop armies of thousands during a full-on assault. Everything has its limits, and there is no single solution that can counter all sizes of enemy forces.

The true purpose of the Great Wall was to prevent smaller-scale raids, typically involving groups of dozens or hundreds.

A 2,000-year-old Han Dynasty document, the Ju Yan Jian (居延简), classifies the Xiongnu invasions into three levels of severity, each corresponding to a different beacon fire signal.

Similarly, the Wujing Zongyao (Complete Essentials for the Military Classics) from the Northern Song Dynasty also categorized invading forces into three levels, “The scale of southern barbarian invaders is divided into three levels.”

This indicates that the ancients didn’t create these categories arbitrarily. They were based on observed patterns and the recognition that invasions typically fell into certain size brackets.

What’s crucial to note is that the upper limit of these categories was several thousand soldiers. This is a key boundary; any enemy force smaller than this was considered small to medium-sized, while anything larger was classified as a large-scale army, which was beyond what the Great Wall could effectively stop.

Historically, every autumn, Central Plains dynasties prepared for “autumn defense” because this was when northern nomadic tribes’ horses were well-fed, making it ideal for long-distance campaigns. During this period, nomads would rally scattered tribes across the grasslands, uniting under tribal coalitions to launch raids southward, using the power of their combined forces to break through the Great Wall’s defenses.

In response, the dynasty would mobilize troops to the border in advance, stationing them there to minimize the losses from large-scale invasions and raids. Only as winter neared its end would the troops begin to withdraw. These large-scale military deployments and defensive operations were costly in terms of resources, money, and manpower.

From 1629 to 1642, over the span of 13 years, Huang Taiji led the Later Jin army of tens of thousands beyond the Great Wall on four separate occasions. His forces plundered countless treasures – gold, silver, silk, and other materials – and captured hundreds of thousands of people.

In the face of such large-scale invasions, the role of the Great Wall was limited. However, such massive incursions were rare, occurring only once every few years.

The Great Wall was primarily built to defend against the more frequent small to medium-scale raids.

Raids involving fewer than a thousand soldiers were the primary threat the Great Wall was designed to defend against.

Organizing cavalry forces of thousands was costly and difficult, whereas assembling groups of dozens was much easier. A single tribe could quickly gather such a force with members who were trusted and familiar with each other, making battlefield coordination smoother. Similarly, a force of several hundred could be swiftly formed by combining neighboring tribes.

These smaller-scale raids didn’t need to wait for autumn when their horses were well-fed, they could happen at any time.

This is why small to medium cavalry raids were the true daily threat to the borderlands. Not only were they more frequent, but they were also more unpredictable.

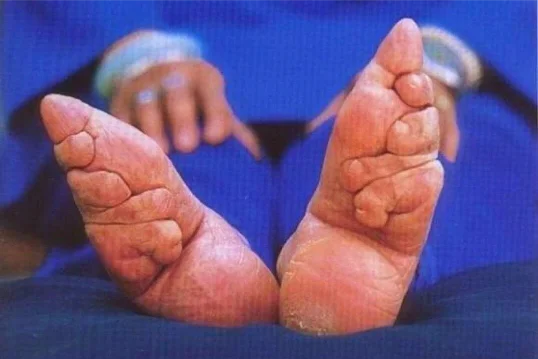

When smaller cavalries came up against the Great Wall, which stood several meters high, breaking through wasn’t as simple as it might seem.

The wall wasn’t made of soft mud, but of compacted, hard-packed earth which had withstood thousands of years of weathering. Destroying it required significant manpower and time.

Even if the raiders managed to create a breach, it could cause a hazard for them as the defending forces would know the exact location of the breach, allowing them to ambush and encircle the invaders.

As the cavalry dismounted and labored to break through the wall, they would likely be spotted by patrols or watchmen on the beacon towers. At that point, the signal fire would be lit, alerting nearby forts and villages. The beacon network would relay the message, notifying the surrounding military outposts to prepare for battle.

Under this joint defense system of beacon towers and the Great Wall, the cavalry’s primary advantage – its ability to raid quickly and unpredictably – was greatly diminished.

The Great Wall served as a boundary to trap and encircle invading cavalries.

Upon their retreat, cavalries didn’t typically have enough time to break through a new section of the wall, as the pursuing forces were usually close behind. Even if they had the time, for cavalries who had scattered into smaller groups to evade capture, it would be difficult to muster enough manpower to breach the wall.

Under the pressure of pursuit, their most common option was to avoid the wall and look for escape routes in other directions where their chances of survival were higher. However, if they didn’t cross the Great Wall, they would eventually be trapped inside its encirclement – a situation where capture was only a matter of time.

If they risked returning to the original breach, they were likely to encounter ambushes and blockades, where defending forces could intercept and annihilate them.

Thus, for cavalries who had crossed the border, the Great Wall represented a formidable and effective threat that could trap and encircle them, preventing their escape and leading to their eventual destruction.

This also answers our earlier question: Why did nomadic people also build their own walls?

Although their simpler versions lacked beacon towers, they still played a crucial role in containing and annihilating small to medium-sized enemy forces. The walls limited the movement of cavalries and delivered lethal blows to invaders, ensuring they couldn’t return home.

Only by imposing such a threat could they deter their enemies from casually invading their territory. Thus, the Great Wall was a structure with significant deterrent power.

Summary of the Great Wall’s military defense

The Great Wall was not designed to block large-scale invasions involving thousands or tens of thousands of soldiers. However, it was highly effective at slowing down small to medium-scale raids which were more frequent. This delay gave defenders time to detect the enemy, organize forces, prepare defenses, and gather reinforcements. Moreover, during counterattacks, the wall provided strong support for surrounding and eliminating the enemy.

At this point, we have thoroughly analyzed the military defensive functions of both the beacon towers and the Great Wall.

However, one critical question remains: Why were some sections of the Great Wall built on steep, rugged mountains?

Near Jinjiazhuang Fort, beacon towers were built on the mountain ridges, but the continuous wall was constructed on the plains below. This design had several advantages as it reduced costs while still preserving the ability to provide warning, delay, and support for surrounding the enemy. Constructing the wall on the plains was already costly, but building it on the mountain ridges would have increased the difficulty and expense even more.

If you were a nomadic invader, would you bypass the wall on the plains and go to the trouble of breaching a section high up in the mountains?

The design near Dabaiyang Fort is similar. The wall wasn’t built directly on mountain ridges but instead took advantage of the terrain, using valleys between mountains to construct multiple passes. This approach minimized construction costs while maximizing effectiveness.

Yet, despite this logic, we still see large portions of the wall built atop mountain ridges, many of which are difficult to access. Constructing the wall on these high ridges was much more expensive, but the military benefit didn’t increase proportionally.

So, why did the ancients undertake such costly projects when the military benefit was minimal?

If we analyze this solely from a military defense perspective, it’s difficult to explain these decisions. To understand why the Great Wall was built in such challenging locations, we must move beyond military factors and introduce another key function of the wall: economic warfare and trade revenue.

Trade wars are not just a modern phenomenon – they were also highly effective in ancient times.

As The Art of War says: “Hence to fight and conquer in all your battles is not supreme excellence; supreme excellence consists in breaking the enemy’s resistance without fighting.”

Economic blockades and trade warfare offered a way to subdue the enemy with minimal cost and loss of life.

In the upper left corner of the diagram below, you’ll notice a small square city marked “Ma Shi”. This was an old market where trade occurred between nomadic tribes and the dynasty. The Ming Dynasty once closed these markets to the Later Jin, imposing an economic blockade. During the late reign of Nurhaci, the cost of rice in Liaodong skyrocketed to eight taels of silver per dou, and fabric prices soared to nine taels per bolt, with fine silks at 200 taels a piece still being unavailable.

Whether in ancient or modern times, economic warfare can devastate an enemy’s economy and cause social unrest, leaving them unable to wage war.

By thinking in terms of economic warfare, we can better understand why sections of the wall were built several meters high, even on mountaintops. While such sections may not have provided much defense against military invasions, they were highly effective at blocking trade.

- While the wall might not withstand a full military assault, it was more than sufficient to control the flow of merchants. By restricting the free movement of people and goods, the wall could enforce a trade monopoly.

- The wall could reshape the economic landscape by funneling all trade through a few key checkpoints, thereby controlling commerce and imposing an economic blockade on the regions beyond the wall.

- The passes along the Great Wall became critical nodes in the trade network, where the state could levy heavy taxes on trade, generating revenue to offset the costs of building and maintaining the wall.

Thus, the Great Wall served two purposes: it was both a military defense and a tool for economic warfare. Both of which were highly effective at weakening the enemy.

Why did the nomadic tribes of the grasslands need merchants?

The grasslands were rich in natural resources, such as horses, cattle, sheep, furs, medicinal herbs, and Qingbai (a type of salt). For nomadic tribes, these items were abundant and not particularly valuable. However, in the Central Plains of China, these goods were sought after and commanded high prices, creating a significant price gap between the two regions.

Conversely, many items produced in the Central Plains were highly desired in the grasslands. Goods such as fabric, alcohol, tea, sugar, silk, porcelain, handicrafts, and cosmetics, which required skilled craftsmanship, were scarce in the grasslands. Nomadic people were eager to exchange their surplus resources for these valuable Central Plains products.

For merchants, business knows no borders – wherever there is a price gap, traders will seek opportunities. This price difference stimulated the rise of trade migration. Large numbers of merchants traveled back and forth between the grasslands and the plains, seeking profit from trade. Over time, these frequent commercial interactions led to the formation of a trade network, and along these routes, settlements and villages naturally emerged. This was the organic evolution of the economic system.

On the grasslands, the Khagan (a nomadic ruler) was the largest supplier of goods to merchants. The Khagan traded grassland resources for large quantities of Central Plains products. While some of these goods were for his personal use, a more critical function was to distribute them to tribal leaders. The Khagan’s supply of resources came from these leaders, so maintaining good relations with them was essential.

Historical records, such as the Manwen Laodang (a set of Manchu official documents of the Qing Dynasty) and the Veritable Records of Emperor Taizong of the Qing (清太宗实录), show that during the enthronement of Huang Taiji, over 3,000 bolts of silk were distributed as rewards, including for the Eight Banners, Mongolian nobles, and the production of official uniforms. A single instance of rewarding 49 Mongolian nobles from the Khalkha and Jarud tribes required 305 bolts of silk. While this might not seem like a lot in the Central Plains, in the remote northeastern region of Liaodong, where silk was a rare and valuable commodity, it represented a significant expense.

The Khagan’s relationship with the tribal leaders was akin to business partners. Investment in the form of goods had to yield profits and rewards. With the wealth they gained, the tribal leaders could secure the loyalty and support of their people. Similarly, the Khagan used this wealth-sharing mechanism to maintain control over the leaders in the grasslands.

In times of peace, steppe empires functioned much like a large company, with its main objectives being production, profit, and distribution. Merchants were their most valued trading partners. Among them, the most successful were the Shanxi merchants (晋商) who conducted business not only along the Nine Borders but also with Mongolia and the Later Jin. Much of the silk used for Huang Taiji’s enthronement was supplied by the Shanxi merchants.

Thus, merchants were vital for maintaining the flow of goods between the grasslands and the Central Plains, supporting both the economy of the steppe empire and the stability of the Khagan’s rule.

How did the Great Wall help restructure the economic ecosystem?

During times of war, the Central Plains dynasties aimed to weaken and dismantle the power of nomadic tribes, employing both military and economic tactics. One common method was economic blockade, which banned the flow of Central Plains goods into the grasslands, thereby weakening the power of the Khagan and the tribal leaders.

However, economic blockades had a side effect – they created scarcity in the market, driving up the prices of goods. While a trade ban could obstruct commerce, it also widened the price gap between the two regions. This price disparity attracted merchants who were willing to risk smuggling to bypass the blockade, seeking alternative trade routes for high profits.

Merchants were highly resourceful. While steep mountain ridges might block the cavalries, they didn’t necessarily hinder merchants. Merchants’ caravans, consisting of oxen, horses, and camels, could traverse thousands of meters of snow-covered mountains and navigate narrow paths along cliffs. Even if the animals couldn’t cross, porters could carry the goods across the borders where their partners on the other side would be waiting to receive them. Merchants’ ingenuity knew no bounds.

Whether crossing mountains, grasslands, or deserts, merchants could always find ways to bypass restrictions. If the government discovered and blocked new trade routes, merchants would explore even more hidden paths through the mountains, gradually forming new trade networks, and the economic ecosystem would naturally adjust and restore itself. The stronger the blockade, the higher the price gap became, which only motivated merchants further as the profits became more enticing.

The Ming Dynasty built many passes, forts, and beacon towers as part of its defenses, but the Great Wall itself was incomplete and disjointed, leaving many gaps. This allowed merchants to slip through easily.

Without a continuous wall, it was difficult for the government to fully implement an economic blockade. To truly achieve this, they needed to connect the sections of the wall and turn these isolated points into a continuous line with no gaps. This was how the Great Wall eventually evolved into the seamless structure we see today, stretching across thousands of miles.

The completion and continuity of the Great Wall became a powerful tool for cutting off trade routes. With a fully connected wall and a system of beacon towers providing warnings and patrols, it became much harder for merchants to sneak through. Merchants, unlike soldiers, were not outlaws willing to risk their lives – they had businesses and families to protect. The risk of being caught or killed while trying to cross or destroy the wall was too great for most to bear.

With the wall in place, merchants were forced to enter the grasslands through official passes, turning these points into open trade hubs. The wall, built on the mountain ridges, made it difficult for smugglers to bypass, and it also served the government by allowing them to collect tariffs. These tariffs provided a significant source of income which could be used to fund the maintenance of the wall and its connected infrastructure.

This answers our previous question: Why did the ancients go to the trouble and expense of building the wall on mountain ridges where the military benefits were minimal?

The answer lies in economic warfare and trade revenue.

During the Wanli period of the Ming Dynasty, scholar Mei Guozhen noted that the northern border region saw goods like silk, furs, and miscellaneous items being transported from Suzhou, Hangzhou, and Huguang to Tianjin and Lugou, generating immense tax revenues. At the trade points, heavy taxes were levied, which often discouraged wealthy merchants from participating due to the shrinking profits.

We can now see the final, connected result of the Great Wall, although we are unable to witness the process of its construction and the full reasoning behind its development. This is akin to possessing a highly developed brain but not fully understanding how its intelligence came to be – you need to piece together evidence to recreate the process.

Thus, the formation of the Great Wall was the result of both military and economic factors. Both were crucial, but neither alone can fully explain the wall’s significance.

Additionally, the wall had an unexpected side effect; by obstructing trade and merchant activities, it triggered massive ecological changes both inside and outside its boundaries, further altering the dynamics of the region.

How did the Great Wall restore the natural ecosystem?

Merchants created trade networks, and at key points along these routes, settlements and villages naturally emerged. These settlements provided services such as lodging and food for passing merchants, while also giving access to essential goods such as salt, tea, and fabric. Just as water nourishes plant life where it flows, human traffic fostered the growth of population hubs where people could settle and thrive.

However, once the Great Wall disrupted these trade networks, many villages far from the official passes began to wither away. But as human activity diminished, the degradation of vegetation also slowed. Trade routes carved through mountains and forests by merchants gradually became overgrown as nature started to reclaim the land.

Those who hike in mountainous areas may have noticed certain trails which are passable in winter become overgrown and difficult to traverse in summer. If a path is left unused for long enough, vegetation will eventually cover the road and render it impassable.

The Great Wall created vast no-man’s lands along its length. Without human activity, roads became overgrown, making travel and passage difficult. This ecological restoration is an unintentional effect of the wall. While its primary purpose wasn’t to restore the natural environment, the lack of human presence allowed the vegetation to reclaim previously trafficked areas.

In some ways, this newly restored wilderness also served a military purpose. These uninhabited areas made it difficult for enemy forces to move or obtain supplies. Even the most powerful army would struggle against dense forests and overgrown trails. In such an environment, the enemy couldn’t march efficiently, and their lack of local knowledge left them vulnerable.

This effect is particularly relevant in the mountainous regions where thick vegetation could hinder military operations. In contrast, in deserts and grasslands where vegetation is sparse, the absence of people created challenges for enemy forces due to the lack of supplies and settlements.

Thus, the Great Wall inadvertently reshaped the landscape along its boundaries, restoring natural ecosystems that had been disturbed by human activity. This process also contributed to the wall’s defensive capabilities by making certain regions difficult for enemies to traverse.

Is economic blockade really an effective strategy against enemies?

The Central Plains dynasties frequently used economic blockades, and they proved to be an effective strategy to balance power on the northern grasslands.

For example, after the Longqing Agreement, the Ming Dynasty began to support Altan Khan of the Mongol Right Wing by opening trade with him. This brought relative stability to the northwest frontier for several decades. At the same time, they continued to suppress the Chahar Mongols of the Left Wing by denying them access to trade, which kept Liaodong in a state of unrest until the Wanli Emperor relaxed the economic blockade.

However, this type of restriction could also backfire, as seen in the late Ming Dynasty.

After the rise of the Jurchens, the Ming imposed an economic blockade on the Later Jin regime, attempting to form an alliance with Lindan Khan of the Mongol Left Wing to counter the Later Jin in Liaodong. However, at a critical moment, the Ming betrayed the Mongols, signing an agreement with Huang Taiji and abandoning the Chahar Mongols. This led to the Mongol tribes fully siding with the Later Jin, facilitating the establishment of the Manchu-Mongol alliance, which later played a pivotal role in the Qing Dynasty’s conquest of China.

The Ming Dynasty also employed economic blockades in other areas, such as their Sea Ban policy (禁海). This attempt to control maritime trade contributed to the Wokou (Japanese pirate) problem along the southeastern coast. When the sea ban was lifted, the Wokou raids sharply declined. Why was this?

Most of the so-called Wokou weren’t actually Japanese but Chinese.

These Wokou were originally private Chinese merchants who had accumulated significant wealth through maritime trade. Their trade extended to Japan, Southeast Asia, India, the Arab world, and European countries like the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain. The sea ban transformed these legitimate traders into pirates, essentially turning them into maritime nomads. They not only smuggled goods for higher profits by avoiding tariffs but also frequently raided coastal counties, creating severe problems.

The Ming Dynasty’s simultaneous battles against the northern Mongols and southern pirates (referred to as “Southern Wokou” and “Northern Mongols”) show that the economic blockade wasn’t ineffective – it was actually too effective. The huge price gaps caused by the blockade made profits too tempting to resist. While small merchants might avoid the risk, larger, more organized, military groups were willing to take the gamble, turning economic blockades into triggers for conflict.

It wasn’t until the Longqing Reforms were implemented, which re-opened trade with the Mongols, that the Ming Dynasty experienced a relatively peaceful relationship with the Mongol tribes. Additionally, lifting the sea ban during that period had global implications. At the time, Spain had just discovered the return route from Manila to the Americas, bringing an influx of American silver into China. In return, Chinese goods were shipped from the Americas to Europe, yielding immense profits. This trade brought about dramatic changes to China’s monetary system and marked the first instance of truly global trade.

Later, the Qing Dynasty attempted to use economic blockades to control Western powers. For example, the Treaty of Kyakhta (1727) between China and Russia established a trade market in Kyakhta, Mongolia. However, due to ongoing conflicts between Russia and the Dzungars, China paused this trade market ten times between 1744 and 1792.

In 1839, the Daoguang Emperor instructed Lin Zexu, who was responsible for enforcing the opium ban in Guangdong, to take a hard stance against foreign powers:

“If they continue to defy us, we should cut off their supply of tea and rhubarb and permanently ban trade. Let them fear the consequences.”

We all know how that story ended – with the Opium War and the eventual collapse of the Qing’s isolationist policies.

The Ming and Qing dynasties’ use of economic blockades, inherited from the strategies of the Great Wall, could be highly effective in controlling and weakening enemies. However, if not handled properly, these blockades could also become triggers for war, leading to disastrous consequences.

A more farsighted figure was Li Hongzhang, who 30 years later had a much broader understanding of the issue. In his 1872 memorial, “On the Necessity of Continuing the Shipbuilding Program”, he wrote:

“For over a century, European countries have pushed through India into the southern seas, and from there to the northeast, penetrating the very heart of China’s borders. Everything that has never been recorded in history, all that has never been touched by civilization, has come seeking trade with China. Our Emperor, with heaven’s wisdom, has established trade treaties with them, bringing together the entire globe – east, west, north, and south – into China’s grasp. This is the greatest transformation in 3,000 years of history.”

“At this point, talk of ‘expelling the foreign invaders’ is clearly foolish. If we wish to maintain peace and protect our territory, we cannot rely on empty rhetoric.”

“The more we learn from their methods, the stronger we will become. Who’s to say that, a century or more from now, we won’t be able to ‘expel the foreign invaders’ and stand strong on our own?”

“Li Hongzhang’s vision was bold and pragmatic, foreseeing the global integration that would come to pass. His suggestion to “learn from the West”, strengthen the country, and eventually regain China’s sovereignty was remarkably accurate.”

“Thus, while economic blockades were a powerful tool of control, if misused, they could backfire and lead to conflict. The key was understanding when and how to use them effectively, without triggering the very wars they were meant to prevent.”

Conclusion

- Beacon towers provided crucial information about the enemy’s timing, location, and numbers, reducing the uncertainty caused by cavalry raids.

- The Great Wall was effective at blocking the most common small- to medium-sized raids of enemies, but it couldn’t stop larger forces.

- Although not very tall, the Great Wall was a highly effective fortification for monitoring, delaying, and encircling the enemy.

- The sections of the wall built on mountaintops played a significant role in trade warfare, preventing merchants from bypassing economic controls.

- The Great Wall and its passes allowed the government to control the flow of people, goods, and information, while also collecting substantial tariffs.