Before we begin the article, I have outlined the different ranks of imperial concubines in ancient China to help everyone better understand the concubine system.

The empress holds the highest position, followed by the imperial noble consort, then the noble consort, and lastly the consort.

However, if the empress does not bear a son, and a consort gives birth to the emperor’s first son, that son is often designated as the crown prince. In such a case, the consort becomes the crown prince’s birth mother. Although the empress still retains her superior rank, the birth mother of the crown prince gains increased status and influence in the palace, due to her son being named heir to the throne.

In the article, Wang Shurong is always referred to as “consort” due to the circumstances she faced during her lifetime.

Wang Shurong’s grandson, Zhu Youjiao, wanted to honor his grandmother with the title she deserved during her life. After becoming emperor, he posthumously granted her the title of Empress Xiaojing. This is why Wang Shurong is referred to by different ranks and titles in the text.

Below is a family tree to help everyone better understand the relationships between the key figures.

In July 1958, archaeologists embarked on the final phase of excavations at Ding Mausoleum, one of the Thirteen Tombs of the Ming Dynasty. Ding Mausoleum is the burial chamber of Emperor Wanli of the Ming Dynasty. The Ding Mausoleum is square at the front and rounded at the back, with smooth and pristine stone foundations, all of which reflect the noble status of its long-serving occupant.

Emperor Wanli / Image Source: Wikipedia

The tombs yielded a significant number of valuable artifacts. These included gold and silver items, jade pieces, royal robes, ancient relics, and a yellow embroidered ceremonial robe. Among these artifacts, one item in particular caught the attention of the experts – a phoenix coronet.

Experts named this piece the “Three Dragons and Two Phoenixes Coronet”. It is made of finely lacquered bamboo strips, adorned with kingfisher feathers, and decorated with dangling pearls and gemstones. 95 gemstones hang densely from it, complemented by 3,426 pearls that shimmer in the light. Beyond its priceless value and exquisite craftsmanship, it’s hard to describe it with any other words. The owner of this coronet was Empress Xiaojing.

Empress Xiaojing / Image Source: Wikipedia

Empress Xiaojing, born as Wang Shurong and later known as Consort Wang, was from Xuanhua in the Hebei Province. She was known for her gentle and kind demeanor, as well as her modesty and beauty. Her father had passed his military examination and held the position of a “Baihu” in the Embroidered Uniform Guard (an official of the sixth rank in the military hierarchy), making him a low-ranking military officer. At the age of three, she moved with her family from her hometown to the capital, and when she was thirteen, she participated in a selection process to enter the palace as a concubine. Although Wang Shurong wasn’t chosen, she was recognized for her qualities and wasn’t sent back to her hometown. Instead, she was retained to serve in the Palace of Compassion and Tranquility, where she attended to Empress Dowager Xiaoding, the mother of Emperor Wanli. Wang Shurong was a delicate and obedient girl, quiet and reserved, which earned her the favor of Empress Dowager Xiaoding, who made her a personal maidservant.

Normally, Wang Shurong might have served in the palace for a few years, after which the Empress Dowager would grant her a generous dowry and arrange a marriage for her with a nobleman, allowing her to enjoy a peaceful and happy life outside the palace. However, her fate took an unexpected turn in the ninth year of the Wanli reign. On this particular day, the young and vigorous Emperor Wanli visited the Palace of Compassion and Tranquility to pay his respects to his mother, Empress Dowager Xiaoding. It was here that he noticed the 16-year-old Wang Shurong, who was attending to the Empress Dowager’s grooming. Captivated, the emperor secretly spent the night with her. Soon after, Wang Shurong discovered she was pregnant, but her low status meant no one paid much attention to her situation.

As her pregnancy became more visible, it became impossible to hide. Eventually, she confided in Empress Dowager Xiaoding in a private chamber. Fortunately for Wang Shurong, the Empress Dowager, who herself came from a humble background (she was also originally a maid, and her ancestors were bricklayers), was not only understanding of her situation but was actually thrilled by the news, eager to have a grandchild. The very next day, she summoned Emperor Wanli to discuss the matter. However, the emperor vehemently denied everything and even scolded Wang Shurong. It was only when the court eunuch presented the records of the emperor’s daily activities that he reluctantly admitted to having spent the night with the young maid.

Empress Xiaoding / Image Source: Wikipedia

The Empress Dowager said, “Emperor! If Wang’s child is a boy, he will be my eldest grandson, and you should elevate Wang’s status.” Under pressure from the Empress Dowager and the traditional belief of “a mother’s rise in status due to her son,” Emperor Wanli had no choice but to promote Wang to the rank of Consort. On August 11th of that same year, Consort Wang gave birth to a boy, who would become the Wanli Emperor’s eldest son, Zhu Changluo. However, two years later, in the 14th year of Wanli’s reign, his favorite concubine, Consort Zheng (Zheng Miaojin), also gave birth to a son, Zhu Changxun.

Consort Zheng had been selected for the palace through a beauty contest. In August of the 9th year of Wanli’s reign (1581), the then 17-year-old Zheng Miaojin from Daxing County was chosen for her outstanding beauty. The following year, she gave birth to the emperor’s second son, Zhu Changxu, who unfortunately died in infancy, and she was subsequently promoted to Noble Consort. Zheng was exceptionally beautiful, and she quickly became Wanli’s favored companion, eventually being elevated to the rank of Consort De(a kind of rank name in consort sytem). Emperor Wanli was deeply enamored with the charming and flirtatious Noble Consort Zheng, and the two were inseparable. After she gave birth to the third prince, Zhu Changzhi, she was further elevated to Imperial Noble Consort, which only intensified Wanli’s dislike for Consort Wang and her son. He always believed that Consort Wang had used the Empress Dowager’s influence to rise in rank and that she had “seduced” him into fathering Zhu Changluo.

Emperor Wanli was further influenced by Imperial Noble Consort Zheng, who repeatedly urged him to make their son, Zhu Changxun, the crown prince. This move sparked strong opposition from the court officials and Empress Dowager Xiaoding. The officials cited the “Ancestral Instructions of the Ming Emperor” and the “Collected Statutes of the Ming Dynasty” which stated, “If there is a legitimate heir, he should be the successor; if there is no legitimate heir, the eldest son should be chosen.” Since neither Zhu Changluo nor Zhu Changxun were born of an empress, the officials argued that the eldest son, Zhu Changluo, should be made crown prince. Empress Dowager Xiaoding also advised the emperor to follow the ancestral traditions, reminding him, “Consort Wang has ensured the continuation of the Zhu family line, contributing to the stability of the Ming dynasty. Why not promote her to Imperial Noble Consort? Is her son not your own?” However, the emperor stubbornly insisted that Wang was merely a maid and argued, “The empress has no sons. If a maid’s son is made crown prince, wouldn’t that mean the future heir to the Ming dynasty was born of a lowly maid?” Upon hearing this, Empress Dowager Xiaoding, moved from sorrow to anger, threw her cane down, slapped Emperor Wanli (as recorded in unofficial histories), and scolded him, saying, “Ungrateful son! Have you forgotten that you, too, were born of a maid?”

Faced with pressure from the Empress Dowager and the court officials, Emperor Wanli decided not to name a crown prince. The officials were deeply worried, and the court became divided into the “Eldest Son Faction” and the “Consort Zheng Faction.” The dispute over the crown prince dragged on for fifteen years, with Emperor Wanli determined to appoint Zhu Changxun, the son of Imperial Noble Consort Zheng, as crown prince, while the court officials, firmly upholding ancestral traditions, supported Zhu Changluo, the eldest son. This prolonged conflict, known as the “Struggle for the Crown Prince,” significantly impacted the Ming dynasty’s fate. During this period, four Grand Secretaries were forced out of office, over ten high-ranking officials were implicated, and more than 300 central and local officials were affected, with over 100 being dismissed, demoted, or subjected to harsh punishments, including military exile. The Wanli Emperor’s harem was also in turmoil, as Imperial Noble Consort Zheng, in her bid to make her son crown prince and herself empress, coerced Emperor Wanli into swearing an oath in a Taoist temple. This led to accusations from upright and outspoken officials that she was meddling in state affairs. Ultimately, after exhausting all her means, Imperial Noble Consort Zheng became increasingly frustrated, frequently arguing with Wanli. The emperor, caught between his authority and the opposition from court officials, became deeply disillusioned and distrustful of his ministers, leading him to neglect his duties for over twenty years, during which he rarely attended court or dealt with state affairs. This neglect contributed to the decline of the Ming dynasty and marked the end of the prosperous “Wanli Restoration”. This term refers to the period during the early reign of Emperor Wanli, which was characterized by relative prosperity and stability. During this time, the Ming economy recovered, national power was strengthened, and the political situation was relatively stable, hence the name “restoration”.

It wasn’t until October 1601 (the 29th year of Wanli’s reign) that Wang Shurong’s 19-year-old son, Zhu Changluo, was finally appointed as Crown Prince. As was customary, his mother, Consort Wang, was promoted to Imperial Noble Consort. However, this did not mark the end of the struggle over the succession. Emperor Wanli, influenced by Imperial Noble Consort Zheng, still entertained thoughts of replacing the crown prince, delaying the process of sending his favored son, Zhu Changxun, to his own princely fief. Meanwhile, Zhu Changluo was treated very differently. Although he was allowed to start his studies at the age of thirteen after much effort from the ministers, he soon dropped out and remained out of school for a long time. As a result, Zhu Changluo became the least educated of all the Ming emperors. During his time as Crown Prince, he suffered from neglect, and five of his seven sons died young (only his eldest son, Zhu Youjiao, and fifth son, Zhu Youjian, survived).

Although Zhu Changluo won the “Struggle for the Crown Prince” and was designated as the heir to the Ming dynasty, his mother, Consort Wang, suffered tragic treatment.

After Zhu Changluo was made Crown Prince in October 1601, he moved to the Ciqing Palace. Before this, Zhu Changluo (and his sister) had lived with his mother, Consort Wang, in the Jingyang Palace, one of the most remote and desolate places in the Six Eastern Palaces of the Forbidden City. The family lived there for thirteen years, relying on each other for survival. Under the “careful supervision” of the powerful Imperial Noble Consort Zheng, they lived a life of near isolation, constantly under the watchful eye of Emperor Wanli. Consort Wang was in a state of constant fear for her son’s safety, watching over him every night and sleeping beside him. Despite living so cautiously, Imperial Noble Consort Zheng still slandered Zhu Changluo, frequently accusing him of harassing palace maids and causing disorder in the harem. It was only thanks to Consort Wang’s desperate defense and the protection of his grandmother, Empress Dowager Xiaoding, that Zhu Changluo managed to survive and grow into adulthood.

Jingyang Palace

After Zhu Changluo was made Crown Prince and moved out, Consort Wang was left alone in Jingyang Palace, which only increased the hatred that Wanli and Noble Consort Zheng had for her. For ten years, she and her son were not allowed to see each other. In September 1611 (the 39th year of Wanli’s reign), Consort Wang fell gravely ill. Zhu Changluo knelt and tearfully begged Emperor Wanli to let him see his mother one last time. The cold-hearted emperor said nothing, merely nodded, and didn’t even look directly at his crying son.

There were many times when Zhu Changluo passed by Jingyang Palace, but he could only gaze at it from a distance, wondering day and night if his mother was healthy, if she had enough to eat, or if she was even still alive. He knelt outside Jingyang Palace countless times, praying that his mother would survive and would live to see the day when he became the Emperor of the Ming dynasty. Many times, he imagined rushing into the palace to see her, but he quickly dismissed the thought. If he did so, it would provide an excuse for Imperial Noble Consort Zheng to abuse his mother even more, and his position as Crown Prince, already precarious, would be further endangered, which would put both him and his mother at risk.

With his father’s reluctant approval, Zhu Changluo finally returned to Jingyang Palace. He brought with him a food box filled with his mother’s favorite snacks, especially her beloved osmanthus cakes. As he approached the palace that had haunted his dreams day and night, tears welled up in his eyes. According to unofficial records, he saw that the two lacquered doors of Jingyang Palace were covered in peeling paint and secured with a rusty iron lock. Weeds grew everywhere, and bird droppings were scattered all around. Zhu Changluo ordered the eunuchs to find the key, but it no longer worked on the rusted lock, which hadn’t been touched in ten years. In desperation, Zhu Changluo had the eunuchs bring an ax to break the lock, and together they pushed open the palace doors.

What Zhu Changluo saw inside the main hall left him in shock. The hall was in disrepair, with a musty smell filling the air. In one corner, two broken copper basins caught water dripping from the leaky roof. Dust covered the golden bricks on the floor, and the heating system was blackened by soot. Sunlight streamed in through the open door, illuminating the floating dust particles, casting them as golden threads across the room. It was as if these particles were silently narrating his mother’s fierce will to survive. In another corner of the hall, an old mosquito net hung over a bed where the frail, emaciated, and gray-haired Consort Wang lay.

Zhu Changluo broke down completely. He couldn’t believe what he was seeing. He had seen the lavish palaces of Imperial Noble Consort Zheng, yet his own mother, who held the same title, lived in conditions worse than a punished maid. He couldn’t fathom how she had survived these ten years of hardship. The elderly eunuch beside him pointed to the frail woman and, with a tearful voice, informed Zhu Changluo, “Your Highness, the Imperial Noble Consort has suffered greatly,” as all the palace attendants knelt and wept. With tears in his eyes and a trembling voice, Zhu Changluo quietly said, “Mother, your unfilial son, Zhu Changluo, has come. I… I am late.”

Suddenly, Consort Wang opened her eyes, sat up, and frantically reached out with her hands, saying, “My son, my son, where are you? How did I lose you?” Zhu Changluo could no longer hold back his emotions and knelt at his mother’s bedside, crying. Consort Wang used all her remaining strength to caress her son’s face. The eunuch beside them tearfully told Consort Wang, “Yes, it’s the Crown Prince who has come to see you!” The eunuch then kowtowed and said to Zhu Changluo, “The Imperial Noble Consort has longed for you day and night; her tears have run dry, and she has cried herself blind!” Consort Wang wept and said to Zhu Changluo, “My son, you have grown up. I can die without regret now.” Mother and son held each other and wept, and everyone in the hall was moved to tears.

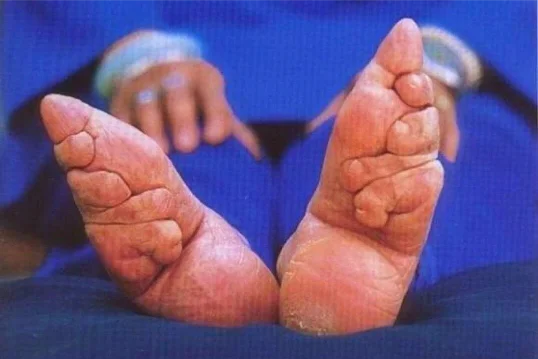

Holding on to life just long enough to see her son one last time, Consort Wang was exhausted. She lay back on her bed, unable to speak another word, but clung to Zhu Changluo’s robe. Her mouth opened and closed as if she still had so much to say to her son (some suggest she might have sensed that people loyal to Imperial Noble Consort Zheng were eavesdropping and chose to remain silent to protect him). Zhu Changluo hurriedly took the food box from the eunuch, broke the osmanthus cake into small pieces, and tried to feed them to his mother, crying, “Mother, please eat. Isn’t this your favorite snack? Please have a bite!” But Consort Wang no longer had the strength to chew, though her hand still tightly grasped Zhu Changluo’s robe. At dusk, after thirty years of suffering in the palace, Consort Wang peacefully closed her eyes, passing away at the age of 46. In her final moments, she had seen her only relative – her grown son, Zhu Changluo, the Crown Prince of the Ming dynasty, who would one day become emperor and be free from anyone’s cruelty. Tragically, even in death, her body had to be prepared under the watchful eyes of those loyal to Imperial Noble Consort Zheng before Zhu Changluo could finally lay her to rest.

When Consort Wang passed away, Emperor Wanli showed no concern and even seemed to feel a sense of satisfaction, as if a long-held grudge had been settled. He was extremely harsh in handling her burial, intending to have her hastily buried in the Eastern Well – a communal burial ground for concubines within the Ming Tombs. Despite her status as an Imperial Noble Consort, her burial items consisted only of a tattered silver pot and a few chipped, gold-plated silver plates – nothing more. This treatment sparked the righteous indignation of the court officials, led by Grand Secretary Shen Yiguan and Grand Academician Ye Xianggao, who repeatedly submitted memorials protesting this injustice. Ye Xianggao argued that the mother of the Crown Prince, an Imperial Noble Consort, deserved a grand funeral. He questioned how she could be buried according to the standards for concubines who had not borne children. Upon hearing this, Emperor Wanli, frustrated by the ministers’ persistence, chose to ignore the issue entirely.

As a result, Wang’s burial was delayed again and again, with her coffin remaining unburied until August of the following year – ten months after her death. Eventually, she was buried in a simple plot on the left side of the Eastern Well, as per Emperor Wanli’s wishes. The low status of her burial and the meager offerings were lamentable.

In August 1620, during the 48th year of his reign, Emperor Wanli passed away, and Crown Prince Zhu Changluo ascended to the throne as Emperor Guangzong. His first act was to posthumously honor his mother with the title of Empress of the Wanli reign. In the first year of the Taichang era (1620), Emperor Guangzong issued an edict to honor his late mother, saying, “I have succeeded to the imperial throne and now rule the empire. As I reflect on my origins, I am deeply moved by the boundless grace of my mother. When I was Crown Prince, I failed to fulfill my filial duties. Now, as emperor, I deeply regret this and wish to express my boundless affection. The Ministry of Rites is to carefully deliberate and report back.” However, the new emperor unexpectedly died after only one month on the throne, during the infamous “Red Pill Case.” After his death, the court was embroiled in the “Palace Relocation Case,” and the ceremony to honor his mother was never completed.

It wasn’t until Zhu Changluo’s son, Zhu Youjiao ascended the throne to become Emperor Xizong, that the matter was addressed. Censor Wen Gaomo submitted a memorial exposing the crimes of Imperial Noble Consort Zheng, accusing her of causing Empress Xiaojing’s death in grief without a final farewell. Emperor Xizong, grateful for his grandmother’s kindness, carried out his father’s posthumous edict, officially honoring his grandmother (Wang Shurong) as Empress Xiaojing. On September 13th of the first year of the Taichang era (1620), he formally conferred upon her the title of “Empress Xiaojing Wenyijingrang Zhenzi Cantian Yingsheng”. This title is an honorific given to a deceased empress, composed of multiple terms that praise her virtues and qualities. Each word in the title represents specific attributes, such as filial piety, gentleness, reverence, modesty, chastity, and kindness. These titles are used to express profound respect and admiration for the empress’s character and her contributions to the imperial family.

Empress Xiaojing’s seal was placed in the imperial records and in October 1620, her coffin was moved from the Eastern Well and reburied in the underground palace of Ding Mausoleum, alongside Emperor Wanli. She was also provided with three large chests of burial items. It wasn’t until the 11th year of the Chongzhen era (1638) that the jade seal and jade records were found in the Imperial Household Department and presented to the ancestral temple by order of the Chongzhen Emperor, finally allowing Empress Xiaojing’s spirit to rest in the Ming Ancestral Temple.

Upon ascending the throne, the young Emperor Xizong, reflecting on the sufferings of his father and grandmother, specially commissioned exquisite burial items to be placed in Empress Xiaojing’s tomb, to compensate for the hardships she endured during her lifetime.

Among these burial items was the “The Three Dragons and Two Phoenixes Coronet”.

Today, this coronet is quietly displayed in the Palace Museum, radiating brilliance, with its lacquered silk and delicate craftsmanship silently telling stories of the past.

Unfortunately, though the coronet is beautiful, Empress Xiaojing never had the chance to wear it during her lifetime.