The Palace Museum in Beijing is undoubtedly a must-visit destination for anyone traveling to the city. This grand palace, standing at the heart of Beijing, is not only a brilliant gem of ancient Chinese culture and art but also a treasure of the world’s cultural heritage. Since opening to the public in 1925, the Palace Museum has attracted countless visitors from both China and abroad, thanks to its vast collection of cultural relics and profound cultural significance. Among these precious artifacts, twelve items stand out as particularly noteworthy. These pieces are revered as the Key Highlights of the Collections in the Palace Museum, each one bearing a rich history and culture, and shining with eternal artistic brilliance.

Table of Contents

- The Gold Cup of Eternal Stability

- The Three Dragons and Two Phoenixes Coronet

- Large Polychome-glazed Vase

- One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains

- Along the River During the Qingming Festival

- Jade Mountain Carving with Design of Yu the Great Controlling the Waters

- Wood Clock with Immortals Extending Wishes for Longevity in Pavilion

- Cloisonne Enamel Lotus Censer with Elephant-trunk Handles

- Lang-Kiln Red-Glazed Vase

- Gray Jade Censer with Dragon Carving

- Yaxu Rectangular Vessel (Ya Xu Fang Zun)

- Kesi Tapestry of Plum Blossoms and Magpies in Winter

The Gold Cup of Eternal Stability

The Gold Cup of Eternal Stability

The Gold Cup of Eternal Stability is a gold artifact from the Forbidden City. This rare and exclusive wine vessel was used by the emperor, symbolizing the everlasting stability of the Qing Dynasty’s territory and rule.

The decoration of the cup is exceptionally luxurious, featuring intricate designs made with fine gold threads, gold sheets, and precious stones such as coral, jade, and agate. These embellishments give the cup an incredibly delicate and opulent appearance. The rim of the cup is adorned with two hornless dragon handles, and the base is supported by three elephant-trunk-shaped legs. One side of the cup is engraved with its name “Gold Cup of Eternal Stability,” which symbolizes national unity and prosperity, while the other side states “Made in the Qianlong Reign.”

This gold cup is considered one of the most treasured small-scale artifacts in the Forbidden City, regarded as “the pinnacle of gold and silver craftsmanship in China and the world,” and as “an invaluable, rare treasure.” According to records from the Qing Imperial Household Department, Emperor Qianlong placed great importance on the production of the cup. The cup required 20 taels of gold, 11 pearls, 9 rubies, 12 sapphires, and 4 pink tourmalines. Before production could begin, a design sketch was submitted for Qianlong’s review and approval, and the cup underwent multiple revisions during its creation.

The Gold Cup of Eternal Stability was the official wine cup used by Qing emperors during the annual New Year’s Day Writing Ceremony. This ceremony, held on the first day of the Lunar New Year in the Hall of Mental Cultivation, involved the emperor writing auspicious phrases such as “National Peace and Stability” and “Eternal Unity of the Nation” as a blessing for the empire.

On New Year’s Eve at midnight, the Qing emperor would place the cup on a purple sandalwood table in the bright window of the Yangxin Hall, pour Tusu wine into it, and personally light candles before writing phrases to pray for the dynasty’s enduring stability. This ritual made the cup a highly cherished ceremonial vessel in the eyes of Qing emperors.

The Three Dragons and Two Phoenixes Coronet

The Three Dragons and Two Phoenixes Coronet

On the afternoon of October 20, 1957, archaeologists discovered three coffins in the underground palace of the Ming Dynasty’s Dingling Tomb in Beijing. The coffins belonged to Emperor Wanli, Empress Xiaoduan, and Empress Xiaojing. Among the burial items found in four storage boxes was The Three Dragons and Two Phoenixes Coronet. This exquisitely crafted crown belonging to Empress Xiaojing amazed the world and is now preserved in the Forbidden City.

The Three Dragons and Two Phoenixes Coronet is adorned with numerous jewels, including rubies and sapphires, and a total of 3,426 pearls. However, the luxurious sparkle of these gems is overshadowed by the brilliant green color that dominates the crown. This green hue comes from a traditional craft called Tian-tsui, where the feathers of a kingfisher are used to color jewelry. This method, which originated in the Han Dynasty, combines traditional metalwork with feather artistry. This technique, used to produce the blue color on the crown, involves affixing feathers onto gold or silver bases. Due to the unique texture and iridescence of kingfisher feathers, the color is exceptionally vivid and luminous, and does not fade over time. The feathers on this crown are arranged on stiff paper, forming over 80 layers to give the crown a vibrant, dazzling appearance.

The selection of feathers for Tian-tsui is meticulous. A kingfisher has ten usable feathers on each wing, known in the trade as “big strips” (大条), and eight feathers on its tail, known as “tail strips” (尾条). Both big strips and tail strips can be used in the Tian-tsui process, meaning a single kingfisher can provide around 28 feathers. These must be carefully shaped and selected, making them extremely precious.

To ensure the vibrancy of the colors, feathers should be plucked from live kingfishers. These feathers can display a range of colors under different lighting, from blue-violet to turquoise and deep indigo. The natural texture and shimmering quality of the feathers add to the dynamic and lively effect of the finished piece, which, when edged with gold, further exudes luxury.

If feathers were taken from kingfishers that have died naturally, they have a slight color difference and are generally referred to as “dark strips” (暗条). Due to their less vibrant color, these feathers were rarely used in high-end jewelry. While Tian-tsui did not involve the killing of birds, the process of feather extraction was quite brutal. During the Qing Dynasty, the popularity of Tian-tsui led to a significant decline in the kingfisher population. Today, using kingfisher feathers for jewelry is illegal, and substitutes like goose or peacock feathers are commonly used instead, in what is known as “Imitation Tian-tsui” (仿翠).

Large Polychome-glazed Vase

Large Polychome-glazed Vase

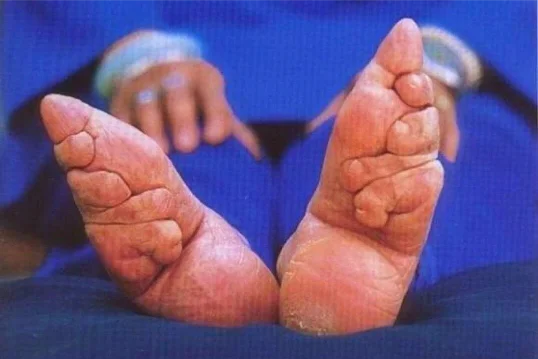

12 patterns on the Large Polychome-glazed Vase

The Large Polychome-glazed Vase stands at approximately 86 centimeters tall, with a dignified form and smooth lines. Its surface is richly decorated yet remains harmonious. The vase integrates dozens of glazing techniques and painting methods, including underglaze blue, famille rose, doucai, and enamel colors. Every hue and stroke embody the wisdom and dedication of the craftsmen. The vase combines both high- and low-temperature glazes and colors, making its firing process incredibly complex. Such a sophisticated technique could only be successfully completed with a thorough understanding of the properties and behavior of the various glazes and colors.

The vase’s body is adorned with patterns that depict natural scenery, each carrying profound symbolism. Bats represent good fortune and lotus flowers symbolize purity. The vase captures the tranquility of landscapes, the vibrancy of flora and fauna, and auspicious motifs that convey blessings, all of which reflect the imperial dignity and the refined aesthetic taste of the royal court.

One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains

One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains – Part 1

One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains – Part 2

One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains – Part 3

One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains – Part 4

One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains – Part 5

One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains – Part 6

One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains is a painting by Wang Ximeng from the Song Dynasty. The artwork measures 51.5 centimeters in height and 11.92 meters in length and is made of silk with blue-green pigments. The painting does not feature a signature, but the inscription by Cai Jing attributes it to Wang Ximeng.

The painting, presented as a long scroll, depicts a vast landscape of continuous mountain ranges and expansive rivers and lakes. The composition includes pavilions, cottages, bridges, and various activities such as fishing, boating, traveling, and birds in flight, all rendered with meticulous detail and vivid expression. The scene is abundant with varied elements, exuding grandeur and a dynamic atmosphere. The texture and light of the mountains and rocks are depicted using hemp fiber and axe-cut techniques. The colors are pure and elegant, with green tones accented by ochre, adding variety and decorative appeal. The painting’s majestic and expansive mood fully captures the beauty and grandeur of the natural landscape, earning it a place among the “Ten Greatest Masterpieces of Chinese Painting.”

Wang Ximeng (1096–1119) was a painter of the Northern Song Dynasty. His exact birth and death dates are unknown. He entered the court’s painting academy in his early teens, initially showing little promise. However, under the direct guidance of art-loving Emperor Song Huizong, who saw his teachable nature, Wang Ximeng quickly advanced in skill, improving his brush techniques and displaying extraordinary talent. It was six months later at the age of 18, that Wang Ximeng created “One Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains.” Unfortunately, he passed away in his early twenties, making him a talented yet tragically short-lived young artist. This painting is considered Wang Ximeng’s “eternal masterpiece,” and he is regarded as a prodigy in the history of Chinese painting, known for a single piece of work that immortalized his name.

Along the River During the Qingming Festival

Along the River During the Qingming Festival – Part 1

Along the River During the Qingming Festival – Part 2

Along the River During the Qingming Festival – Part 3

Along the River During the Qingming Festival – Part 4

Along the River During the Qingming Festival – Part 5

Along the River During the Qingming Festival – Part 6

Along the River During the Qingming Festival measures 24.8 centimeters in height and 5.29 meters in length and was created on silk with color. The artwork is presented as a long scroll, using a scattered perspective technique to vividly depict the cityscape of the Northern Song capital, Bianjing (present-day Kaifeng, Henan). The scroll portrays the daily lives of people from different social classes in the 12th century, as well as animals such as oxen, mules, and donkeys, and carts, sedan chairs, various boats, houses, bridges, and city gates, with each element reflecting the architectural characteristics of the Song Dynasty. The painting holds significant historical and artistic value, serves as a testament to the prosperity of Bianjing during the Northern Song period, and provides a snapshot of the city’s economic conditions at the time.

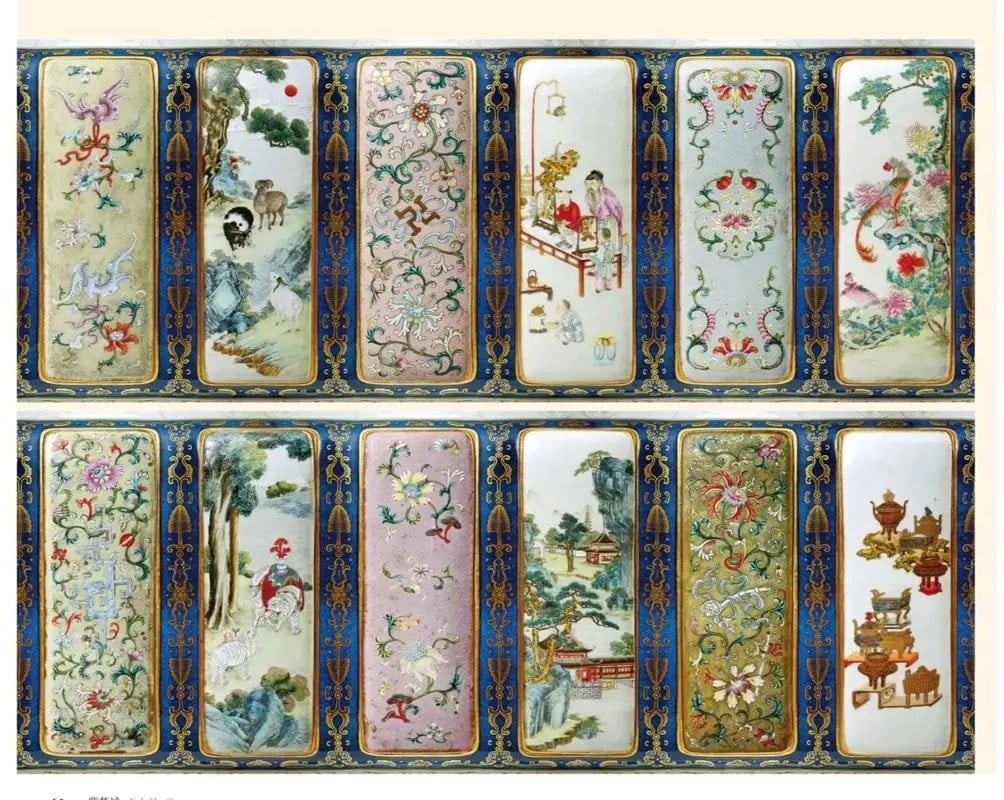

Jade Mountain Carving with Design of Yu the Great Controlling the Waters

During the reign of Emperor Qianlong, a massive jade stone weighing over 6 tons was discovered. This enormous jade had a greenish hue, a fine texture, and a smooth, lustrous surface. Upon hearing the news of this extraordinary discovery, Emperor Qianlong immediately requested the jade be made into a carving for him.

At that time, there were no modern lifting tools, so transportation relied entirely on manual labor and animal power. Over 100 horses were used to pull the cart from the front, while more than 1000 laborers pushed from behind. When they encountered mountains, they had to clear a path; when they encountered water, they built bridges; in winter, they poured water to create ice paths to drag the jade along. Despite their efforts, they could only travel about seven or eight li (approximately 3-4 kilometers) per day. It took over three years to move the jade, an almost unbelievable feat!

There is an old saying: “The Suzhou artisans of the Imperial Workshop are known for their intricate craftsmanship, while the Yangzhou artisans excel in large-scale works.” This indicates that the craftsmen of Yangzhou were particularly skilled at creating large carvings, which is why were selected to carve the jade into a sculpture.

To ensure the carving was completed in time for Qianlong’s 80th birthday, the Yangzhou craftsmen worked in shifts, tirelessly, day and night. It took them seven years and eight months to complete this one-of-a-kind piece, which was then transported from Yangzhou to Beijing.

The jade sculpture depicts the scene of Yu the Great opening up the mountains, leading the people in their efforts to control the floods. On three sides of the mountain, the sculptors used a technique that combined the jade’s natural shape with finely carved figures. The mountain is covered with ancient trees, towering pines, layered peaks, and flowing waterfalls. The jade mountain is filled with numerous figures, all engaged in activities related to flood control. The people, dressed in coarse cloth or even bare-chested, are shown using tools to break through the mountains and move the earth. The muscles in their backs and legs bulge with power as they work.

As for where to place the jade mountain, Qianlong thought carefully and decided upon the Leshou Hall, where he intended to reside as a retired emperor. From the 53rd year of Qianlong’s reign (1788) onward, the jade mountain, known as the Great Yu Controls the Flood, has stood tall in Leshou Hall in the Forbidden City, showcasing its timeless beauty for over 200 years.

Wood Clock with Immortals Extending Wishes for Longevity in Pavilion

This clock is both beautiful and intricate, with a novel and unique design carrying positive phrases that greatly pleased Emperor Qianlong. According to records from the Imperial Clock Workshop, this clock was commissioned by Qianlong in the eighth year of his reign (1743) and was made by Western craftsmen in the workshop. The emperor provided specific instructions for the modifications, such as using cedar wood with colored lacquer for the pavilions and applying gold to the wooden railings. The workshop revised the design accordingly and submitted it for approval. The final construction was completed on January 6, 1749, taking five years from design to completion. This clock has since become one of the most treasured artifacts in the Beijing Palace Museum.

The clock is designed in a two-story pavilion style lacquered in black, with the base decorated with colorful lacquer and gold-painted patterns. Both levels feature gold-lacquered railings, with the door frames and columns adorned with double dragons playing with pearls. The sides and base of the clock are decorated with gold-painted landscapes and bats.

The upper level contains three doors that open and close. At the hours of 3, 6, 9, and 12, music begins to play, and the doors open. Three brightly dressed figurines slowly emerge to announce the time, then return inside as the doors close automatically. Afterward, the scenes on both sides of the lower clock face come to life, showing “Sea Pavilion Adding Another Pillar” and “The Eight Immortals Celebrating a Birthday.” On the left, towering peaks and pavilions are depicted, with a crane flying in the sky holding a pillar in its beak. On the right, in a serene mountain village, the Eight Immortals present their treasures to an elderly figure, offering birthday blessings. As the clock plays music, the scenes are lively and harmonious, blending the heavens and earth in a unified display. When the music stops, all activity ceases.

Cloisonne Enamel Lotus Censer with Elephant-trunk Handles

The Cloisonne Enamel Lotus Censer with Elephant-trunk Handles dates back to the late Yuan and early Ming Dynasties and is renowned for its exquisite craftsmanship and luxurious decoration. It was part of the Qing Imperial Collection and is now housed in the Beijing Palace Museum, where it is considered one of their top ten treasures. It was made using the cloisonné enamel technique, which involves combining metal wires with enamel colors, followed by firing and polishing processes.

This censer is round with a bulging belly and features elephant-head handles with curled trunks and a ringed base. The neck and belly of the censer are adorned with intricate lotus scrolls and chrysanthemum patterns, showcasing the delicate and masterful decorative techniques. The entire design is ingenious, with lifelike details and vibrant colors, making it one of the most precious examples of ancient Chinese craftsmanship.

Lang-Kiln Red-Glazed Vase

The Lang-Kiln Red-Glazed Vase is a representative piece of ceramic art in the Forbidden City. It stands at 20.8 cm tall, with an opening diameter of 6.1 cm and a base diameter of 9.1 cm.

Lang-Kiln Red (Sang de boeuf glaze) is made using copper as the coloring agent and is fired at temperatures exceeding 1300°C. Due to the high volatility of copper at these temperatures, the range of achievable colors is limited, and the firing process is highly sensitive to factors like atmosphere and temperature. This makes it extremely difficult to produce, with only a few successful pieces emerging from hundreds of firings. This difficulty is reflected in the saying, “If you want to go broke, try firing Lang-Kiln Red.” Even though cost was not a concern when making porcelain for the emperor, the Qing dynasty collection contains few Lang-Kiln Red pieces, and most of them have some imperfections. Truly flawless masterpieces are exceedingly rare.

Gray Jade Censer with Dragon Carving

The Grey Jade Censer with Dragon Carving is from the Song Dynasty and measures 7.9 cm tall with an opening diameter of 12.8 cm. The censer features a dragon intricately carved in a dynamic pose, as if flying and breathing clouds of mist. Surrounding the dragon are shallow carvings of ruyi-shaped clouds, symbolizing good fortune, and the base of the censer is inscribed with a poem by Emperor Qianlong. With its unusual grey hue, this is one of Qianlong’s favorite jade pieces and is considered a pinnacle of Chinese craftsmanship.

Yaxu Rectangular Vessel (Ya Xu Fang Zun)

The bronze Yaxu Rectangular Vessel is from the Shang Dynasty and is one of the most treasured artifacts in the Palace Museum. It is renowned for its unique shape, exquisite decorations, and valuable inscriptions, attracting countless visitors and researchers.

The vessel measures 45.5 cm tall and 38 cm wide, weighing a colossal 21.5 kg. Its design features a wide mouth with four corners on the shoulder, each adorned with an elephant head. There are further animal heads positioned between these. The entire surface of the vessel is decorated with animal mask patterns and Kui (dragon-like) motifs.

A zun is a type of wine vessel that was popular from the early Shang period, through to the Spring and Autumn, and Warring States periods. Square-shaped zun vessels like this one are rare.

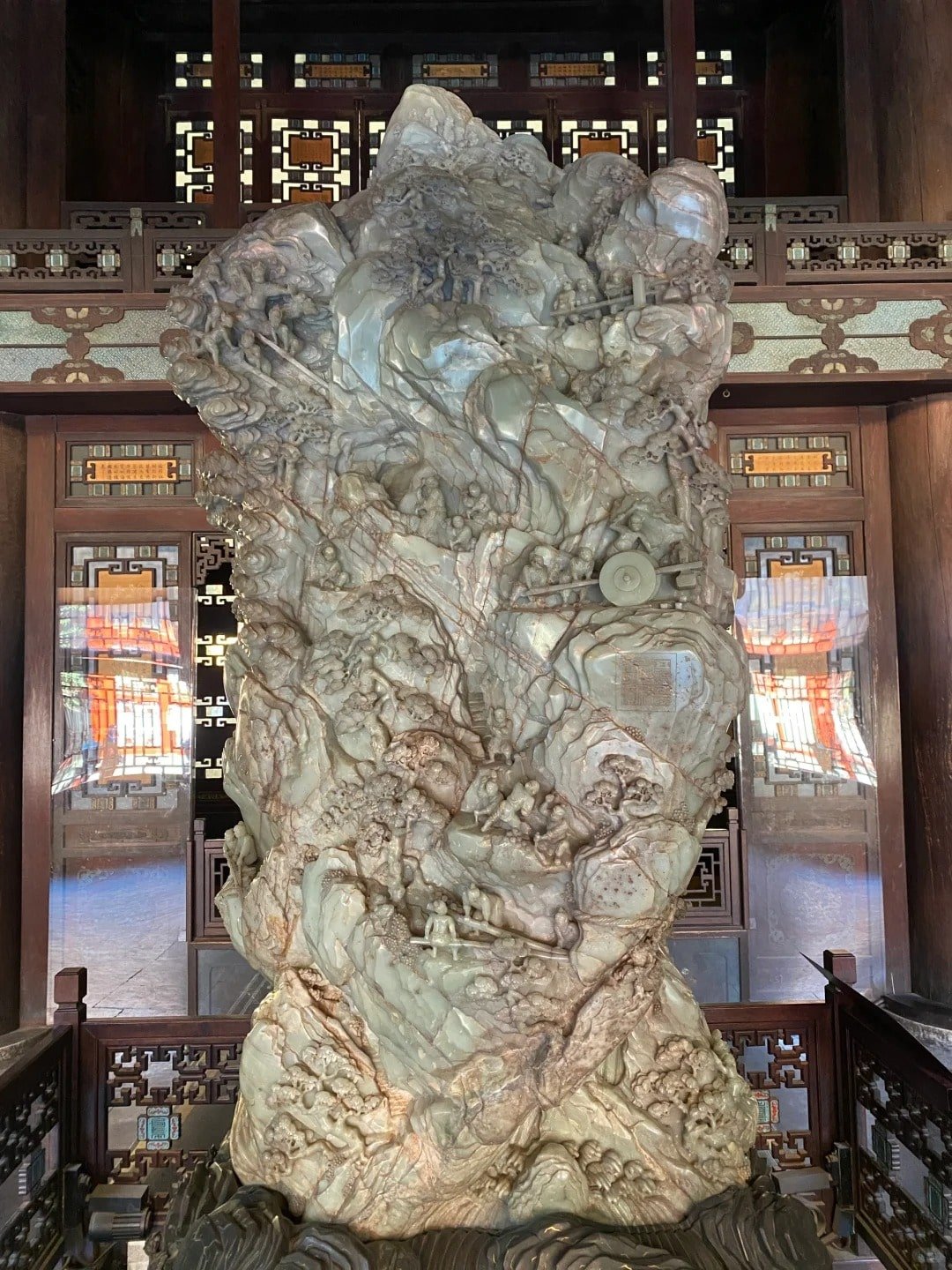

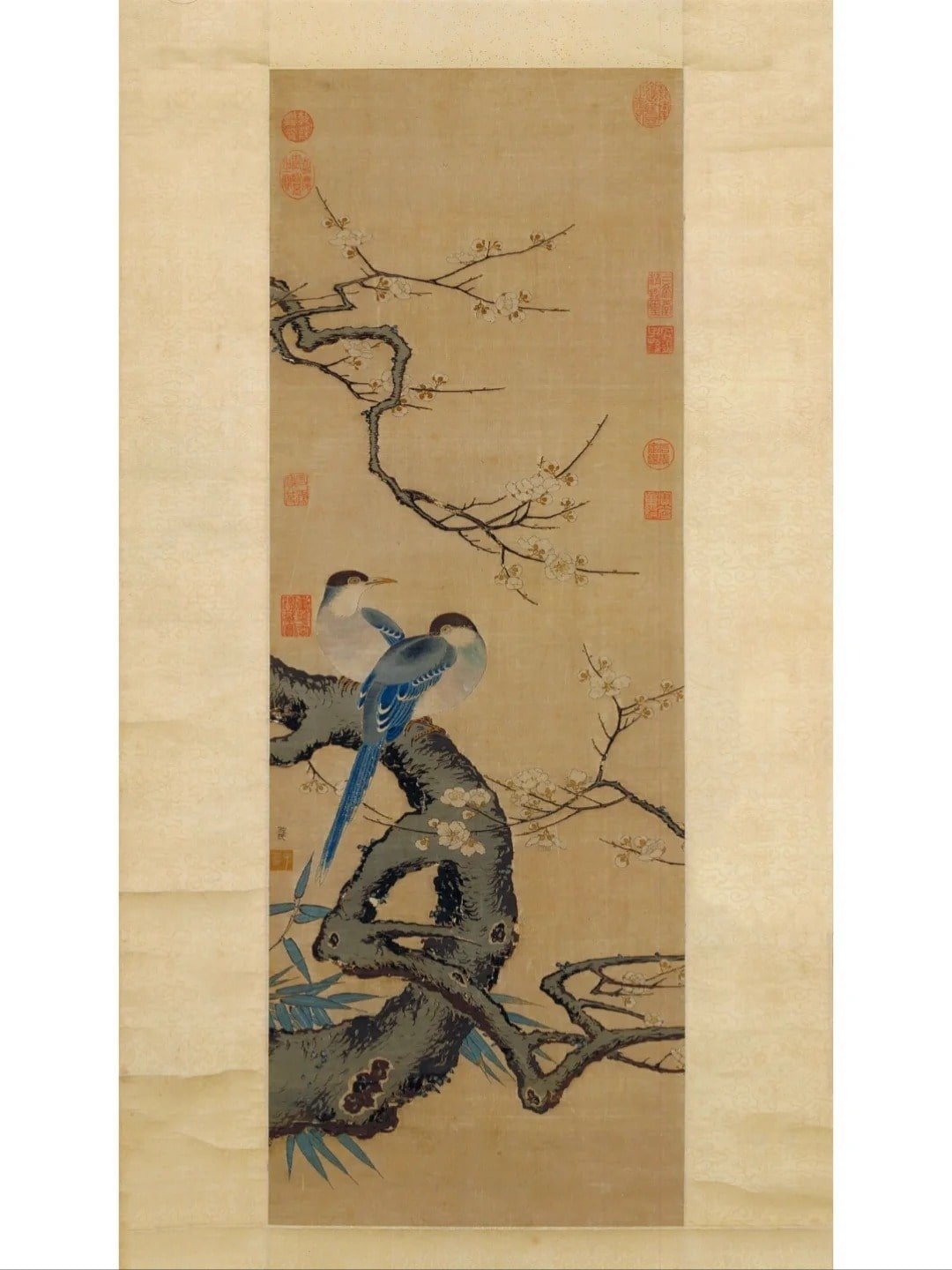

Kesi Tapestry of Plum Blossoms and Magpies in Winter

The Kesi Tapestry of Plum Blossoms and Magpies in Winter is a silk tapestry (kesi) artwork by Shen Zifan from the Southern Song Dynasty, 104 cm tall and 36 cm wide.

Kesi is a traditional Chinese silk weaving technique, known for its warp and weft method. The process is intricate and time-consuming, earning it the reputation of “an inch of kesi is worth an inch of gold” and the title of “the saint of weaving.” Kesi artisans require not only skilled weaving techniques but also a high level of artistic knowledge. Shen Zifan was a renowned kesi master during the Southern Song period.

This painting depicts an old plum tree with blooming plum blossoms, two magpies resting on the tree branches, and a cluster of bamboo. The artwork follows the “court style” of the Song Dynasty, characterized by its clear, elegant composition and rich use of color. The tapestry uses 15 to 16 different colored silk threads, skillfully combined to express a sense of simplicity and antiquity. This piece is one of the few surviving works by Shen Zifan and a representative example of Southern Song Dynasty kesi art.