In my opinion, foot binding is the single most cruel and horrifying social practice in Chinese history—nothing else even comes close. It ruthlessly destroyed the vitality of generations of Chinese women and utterly robbed them of the respect they deserved. It’s beyond infuriating!

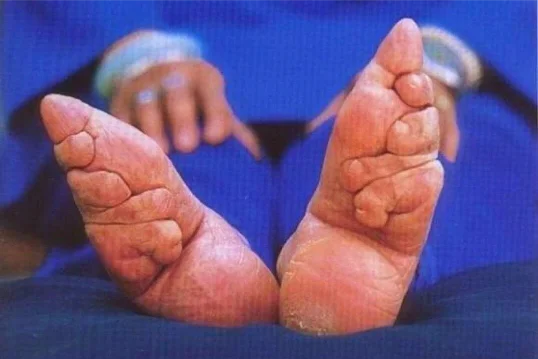

I’ll be honest—being Chinese, even as a man, when I came across historical documents and images depicting ancient women’s feet twisted grotesquely, like permanently shaped high heels—with bones brutally broken, toes bent underneath the sole, except the big toe—it not only made me physically sick but filled me with profound pity and empathy for these women.

Foot binding was a cruel tradition forced upon Chinese women for hundreds of years. It persisted right up until recent times before finally fading out. But it wasn’t merely a cultural tradition—it intertwined deeply with society’s structure, gender roles, and prevailing standards of beauty. In this post, I’ll explore its origins, development, impacts, and eventual disappearance.

The earliest origins of foot binding trace back to the Tang dynasty, specifically to a palace dancer named Yao Niang, favored by Emperor Li Yu of the Southern Tang in the 10th century. Legend says she wrapped her feet in silk cloth and danced elegantly on a lotus-shaped stage, charming the nobles who imitated her. Initially, this early foot binding was just tight wrapping to make dancing movements more graceful—much like modern ballet. Indeed, archaeologists have uncovered women’s shoes from the Yuan and Ming dynasties that were roughly the size of normal women’s feet. It wasn’t until the Qing dynasty that foot binding evolved into the horror we commonly associate it with today—bone-breaking deformities taken to extremes.

There were many reasons behind foot binding, but the most influential was the standard of beauty. In ancient China, women were viewed primarily as family appendages, responsible for childbirth and household chores. Therefore, femininity became synonymous with frailty, submissiveness, and delicate grace. Against this background, bound feet symbolized a refined beauty, believed to make women’s gait gentle, elegant, and alluring. Ancient scholars romanticized small feet (typically around three inches long) as “Golden Lotuses,” associating them with purity and chastity. Small feet thus became the societal standard of feminine beauty, transforming women’s bodies into ornaments designed solely to please men. There was even an old saying: “Only with bound feet can a girl marry—and marry well!”

Ancient Chinese society promoted a deeply patriarchal “men superior, women inferior” ethos. Foot binding was also intended to restrict women’s freedom of movement, forcing them into domestic confinement, reinforcing the traditional separation of male and female roles. I’ve even come across absurd claims suggesting that bound feet prevented women from venturing outside, effectively lowering opportunities for infidelity or running away with another man. Indeed, marriages in ancient China were mostly arranged by parents, rarely based on love or mutual affection.

There’s another, even darker theory: when women’s feet were tightly bound, the resulting muscular tension extended upward, tightening the thighs, buttocks, and even the muscles surrounding the reproductive organs. This grotesque practice was thus believed to enhance sexual pleasure for both partners during intercourse.

Although foot binding was widespread in ancient Chinese society, it was undeniably cruel—a practice of unimaginable pain passed down through generations from mothers to daughters. The process was horrifyingly prolonged and painful.

First came the “trial binding.” Young girls, often only a few years old, would have their feet soaked in hot water to soften the bones. Then, while the feet were still warm, four smaller toes (all except the big toe) were folded beneath the sole. Alum powder was sprinkled between the toes to dry the skin, and long strips of cloth were tightly wrapped, layer after layer, shaping the foot. The cloth was then sewn shut, leaving the foot pointed sharply with the big toe sticking forward. A pointed embroidered shoe was fitted next.

The second stage, “test tightness,” required unwrapping and re-tightening every three days. Gradually, over about six months, toes were repeatedly bent and forced toward the sole. This slow deformation was essential—forcing them quickly would permanently cripple the foot.

The third stage, called “tight binding,” bent the entire foot into an arch. It was the most torturous phase: muscles atrophied, skin festered, and four toes slowly became crippled or even fell off due to necrosis. And the agony didn’t stop there.

The fourth stage, known as “arch binding” or “breaking the waist,” involved tightly wrapping the foot to raise and firmly set the arch, a process lasting another six months. Finally, this created a permanently deformed, bowed foot.

You might wonder: surely no woman willingly chose such a horrifying practice—it must have been imposed by feudal rulers exploiting women? I discovered two differing historical viewpoints. The first argues that authorities in most dynasties, including Ming and Qing, explicitly prohibited foot binding. After the Manchu Qing dynasty took control, they repeatedly issued edicts banning Han Chinese foot binding, yet with minimal success. But why?

Foot binding’s transformation from niche practice to widespread obsession was slow. Originally confined to palace dancers, it spread among the wealthy elite before trickling down to common women. For most ordinary women, foot binding wasn’t punishment but an extremely painful badge of honor and status. During the Republican era, when forceful measures outlawed foot binding, many women—whose lifelong pride and dignity were wrapped up in their bound feet—tragically committed suicide rather than endure the humiliation.

Why did such horrific mutilation become widespread? Ultimately, the roots lay deep within patriarchal ideals. Men dominated society and imposed their warped aesthetic standards onto marriage and morality. Intellectuals romanticized bound feet as markers of virtue, suggesting the smaller the feet, the better the wife—thus transforming a private male fetish into a public virtue.

Additionally, small feet symbolized wealth: women unable to work represented affluent families, enticing common people to emulate elite standards. Unlike beauty, which was largely genetic, foot binding provided an achievable means for a woman to boost her marriage prospects and family honor. Thus, the perverse practice endured and intensified over centuries, subjecting generations of Chinese women to lifelong torment—until finally banned following the founding of New China, freeing women physically and mentally.

Certainly, this liberation wouldn’t have occurred without countless revolutionary martyrs and female heroes who bravely fought and bled for change.

Another controversial theory suggests extreme bone-breaking foot binding was unique to the Qing dynasty and forcibly imposed by the Qing government, established by Manchus—a minority ethnic group, unlike the majority Han Chinese. This perspective argues the brutal form of foot binding was not originally Han culture, but a twisted distortion promoted by Qing rulers, who banned the milder, healthier Song-Ming foot binding practices (which simply shaped feet temporarily, akin to corseting) and instead mandated extreme bone-breaking practices exclusively among Han Chinese. Manchus themselves were forbidden from any form of foot binding.

Why impose such brutal practices? It was strategically designed to control enslaved populations by immobilizing Han women, preventing escape or rebellion. With wives, daughters, and mothers unable to flee, men’s capacity to rebel diminished greatly. Additionally, the Qing deliberately targeted Han cultural identity, imposing Manchu hairstyles and dress upon all Han people. Eliminating Han practices, including milder foot binding styles, was essential in spiritually dominating the Han populace.

While this second theory remains controversial and subject to historical debate, the lesson remains clear:

We must learn from history’s painful scars. Foot binding was a lifelong imprisonment for women, reducing them to little more than livestock.

Finally, let me pay my deepest respect to all the women who have bravely carved light from darkness, planted lotuses in mud, and grown wings within their shackles. Their crushed bones eventually lifted souls to freedom.

True beauty never blooms within cruel restraints; it bursts forth gloriously when we break the chains of destiny!