215 BCE, the 32nd year of Qin Shi Huang’s reign, was particularly special for the Qin Dynasty.

If Qin Shi Huang (born Ying Zheng), had passed away during this year, prior to the controversial decisions he made in later life, he would have been regarded as the greatest emperor in Chinese history, and arguably in world history—without exception!

Why?

Because in this era of imperial rule, his combination of military achievements and civil governance was unmatched.

In 221 BCE, the 26th year of his reign, Qin Shi Huang conquered the six warring states and unified the whole of China.

However, northern nomadic tribes like the Xiongnu were not included in this. Although a powerful force, their nomadic way of life differed from the rest of China, so they were not seen as a civilization.

In addition to his significant military achievements, Qin Shi Huang also changed civil governance. As the first ruler to unify the land of China, he accomplished many important reforms, bringing tremendous benefits for both his existing and future generations.

And we’re not just talking about building dams or bridges, though such projects are indeed impressive.

Qin Shi Huang single-handedly built the foundation and framework for governance that lasted for over two thousand years in China. The decisions he made had a great impact, despite him having no historical precedents to guide him.

Each of his accomplishments could have easily established any other emperor in history as a legendary ruler, praised for centuries.

The story of Qin Shi Huang should be told from a different perspective than that of the rulers who led their nations to ruin. Qin Shi Huang caused chaos beyond measure, yet he also laid the foundation for many years of governance.

It is important that future generations understand the significance of his actions and how they continue to impact the world today.

First is the initial decision he faced: Should he adopt the feudal system or the prefecture-county system?

After unifying the empire, Wang Guan (the then Prime Minister) suggested, “Places like the former states of Yan, Qi, and Chu are too far from our core region in Guanzhong. If we don’t establish vassal states there, I fear it will be difficult to control. You should grant these regions to your sons.”

Wang Guan’s recommendation for a centralized feudal system seemed like a reasonable suggestion. However, Ying Zheng (Qin Shi Huang) was unsure, so he decided to bring it up in a government meeting.

During the discussion, the Minister of Justice, Li Si, shared his thoughts.

Li Si argued, “Back in the Zhou Dynasty, when King Wen and King Wu established the feudal system, most of the vassals were their relatives, all from the same clan. Initially, they all intended to maintain the unity and bond of one big family. But after a few generations, things changed. When they met, they were more like enemies than kin. The bonds of kinship had vanished, and powerful arms had started to emerge. By that point, the Zhou kings could no longer stop them! Now, thanks to Your Majesty’s great strength, you have unified the world. You must not repeat the mistakes of the Zhou Dynasty. Instead, you should adopt the prefecture-county system to keep all power in your hands! If you want to reward the royal family and meritorious officials, you can do so through generous gifts and taxes. Give them wealth, not power. Only by ensuring that no force within the empire can challenge the central government will we have a truly safe strategy.”

Ying Zheng agreed. “This is excellent. Our chief political advisor has the right insight.” He declared, “The endless wars of the past were due to the existence of marquises and kings. We are fortunate that, with the blessings of our ancestors, peace now reigns over the land. We cannot follow the old path of feudalism, which will only breed another cycle of endless conflict. We will proceed as Minister Li has advised!”

With this crucial decision, Li Si helped usher in a new chapter in Chinese history, laying the foundation for a system where unity succeeds division.

From this point onward, the concept of a unified empire became deeply ingrained in the minds of the Chinese people.

Even though there were several chaotic periods that lasted for hundreds of years—for example, during the Three Kingdoms and the Five Dynasties—no matter how fragmented China became or how long it remained divided, there was always a dominant force that eventually reunited the land into a single entity.

In the eyes of future generations, China was destined to be unified. As the saying goes, “The sky cannot have two suns, nor can the people have two rulers.” There could only be one emperor.

This confidence stemmed from the fact that previous dynasties had achieved unity, with some maintaining it for many years.

The first dynasty to set this example was Qin, although its reign was brief.

Li Si’s advice was brilliant; he calculated the cost of ruling by considering the dilution of family bloodlines and the expenses of governance. However, we should acknowledge that, in truth, his suggestion wasn’t all that valuable as the real credit goes to Qin Shi Huang.

Not just because he was the leader, but because this decision was easier said than done.

When Qin Shi Huang made this choice, he was under enormous pressure. At that time, many saw him as a huge risk-taker.

As we mentioned earlier, future generations always aspired to reunify China, no matter how divided it became, because they knew it had been done before.

But, when you consider the reverse of this logic, you’ll realize just how risky Qin Shi Huang’s decision was.

No one had ever achieved a unified empire before.

To the people of that time, the idea of organizing a vast, unified empire seemed utterly impossible.

Why?

Because it was simply too large.

Imagine if today we proposed unifying the entire world into one country. Or even if we attempted to unify all of Southeast Asia into a single nation. Does that seem realistic?

With so many different languages, ethnicities, cultures, and histories, it seems impossible to bring them all together.

The complexity of forming such a massive nation far exceeds humanity’s organizational capabilities today.

People had grown used to over a thousand years of division and the existence of independent states. Asking everyone to suddenly live together in one “global village” would create immense anxiety.

The governance structures that Qin Shi Huang established wouldn’t appear in the West until over 2,000 years later, during the French Revolution. Western nations lagged behind by millennia in this regard.

If Europe had a flat landscape like China’s, it might have stayed unified without even an uprising. If they tried to secede, an army would crush the rebellion in days. This is why, when the Xiongnu were pushed west by the Chinese, or when the Mongols invaded, Europe could only pray!

The crucial role of Ying Zheng (Qin Shi Huang), the “First Emperor”, is starting to become clearer.

At this point, the state of Qin was facing many significant, urgent issues that needed to be addressed.

Don’t believe the idea that the prefecture-county system alone provided a guarantee for ruling such a vast empire.

Even if you gave Europe the prefecture-county system, it still wouldn’t be able to implement its policies far!

The problem wasn’t just about the system, the human mindset is something the prefecture-county system can’t solve.

Military conquest was only the first step; it was cultural unification and political assimilation that would ensure the empire’s stability.

In order to secure his rule over the country, Qin Shi Huang took several steps.

The first step addressed cultural unification and political integration.

So, how were these two issues tackled?

The answer lay in language.

After Qin Shi Huang unified the six states, his empire was twice the size of what it had been before. All this was achieved within a little over ten years—the speed was staggering!

Han, Chu, Qi, Zhao, Yan, and Wei had all lost their countries within a short period. If Qin had taken 100 years to gradually conquer the six states, the integration could have happened more naturally over time.

After all, time is the best way to dissolve barriers. But Ying Zheng accomplished it in just ten years.

And as the first ruler to unify China, Ying Zheng faced challenges far more difficult than any emperor who succeeded him.

He couldn’t rely on establishing a national ideology to guide the culture, as later dynasties would.

Nor could he establish a state religion to unify the faith of the people, as other civilizations might.

He needed to quickly facilitate cultural exchange and political orders throughout the newly conquered lands.

In short, he needed everyone to swiftly identify as Qin citizens and abide by Qin laws.

This was extremely difficult because people spoke different languages, and therefore couldn’t understand each other’s speech or written script.

China’s vast territory, with its diverse landscapes, had fostered many different dialects. Today, when people from northern China visit Guangdong or Hong Kong, it’s almost like going to Japan, as communication through speech is practically impossible. You simply don’t understand what they’re saying.

However, this doesn’t necessarily prevent you from communicating with the locals.

Most of East Asia falls under the influence of Chinese characters (the Hanzi writing system). Even in Japan and Korea, you can often grasp the meaning of written words—even if they are slightly twisted or complex—because they use recognizable Chinese characters.

The situation that Qin faced back then was far more difficult than what we see in modern East Asia. Not only were people from different regions unable to understand each other’s spoken language, but they also didn’t recognize one another’s written characters.

People traveling from one former state to another often needed to bring a translator.

As for the idea of a unified spoken language, it was practically unthinkable. Even today, trying to unify dialects is impossible.

Language cannot be standardized as it’s impossible to quantify.

Think back to when you were young, did you hire a tutor specifically to teach you how to speak? Of course not; you simply picked up the language of your region.

A country could not designate one regional dialect as the national standard and send people from that area around the world to promote it; they would be influenced by local dialects in no time.

Written language is incredibly important, thus Ying Zheng pushed for the standardization of characters.

Once again, it was Li Si (who helped lead all the foundational initiatives of the Qin Dynasty) who took on this task. He based the new standard script on the Qin state’s characters, referencing the six other states to create a new, more uniform, and streamlined script, known as the Qin seal script or small seal script. This became the official standardized way of writing, and the scripts of the other states were abolished.

In addition to the small seal script, Ying Zheng also implemented the clerical script (created by Cheng Miao) as a second, parallel writing system. The clerical script changed the rounded shapes of characters to squared, replaced curved strokes with straight ones, and replaced “continuous strokes” with “disconnected strokes,” transitioning from flowing lines. This script largely became the model for how Chinese characters are written today.

This major advancement made the clerical script easier and faster to write than the small seal script, and it quickly gained popularity across the country, becoming the everyday writing style for common people.

Small seal script became the official Qin standard for imperial edicts and government documents, while non-official documents were copied in the clerical script which served daily use.

From then on, this dual system for official and civilian communication was established.

This applied not only to the characters but also to the writing style. Since carving bamboo slips was difficult and expensive, brevity became essential.

The standardization and simplification of written language not only helped the Qin state absorb the six conquered territories culturally, but it also led to another institution that would influence China for thousands of years: the bureaucratic system.

Nowadays, when we hear the term “bureaucracy,” it’s often negative, symbolizing arrogance, inefficiency, and red tape. However, in its original form, bureaucracy was one of the most important inventions in China.

Once writing had been standardized, the foundation of the bureaucratic system was formed.

This system relied on a specialized group proficient in using standardized characters for effective communication. These were the officials and clerks tasked with implementing national laws, policies, and military strategies.

With a unified script, top-level policies could reach the grassroots level, and resources from local levels could flow upward to the central government. During floods on the Yellow River, a vast workforce could be mobilized to defend the dikes, and in times of invasion, trained forces could be deployed to protect the land.

China began to function as a single entity.

The importance of standardized writing was recognized by later rulers, who strictly controlled any modification of the characters. Dictionaries could only be published by the central authority.

Without control over written language, unofficial, simplified characters would have quickly spread among the people. Left unchecked, it wouldn’t take long for different areas to develop unique and unrecognizable characters, creating cultural and communication barriers that make unity impossible. If the characters fell into chaos, you would be looking at a country where each village acted like its own nation!

Thus, the unification of written language benefited people at the time, and for generations to come, with far-reaching effects.

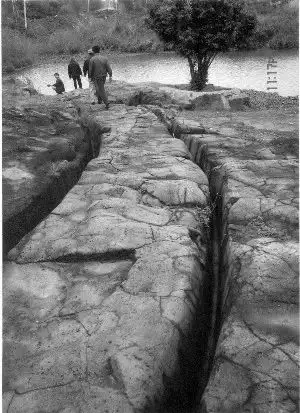

The second step was to standardize vehicle axle width.

The policy of standardizing axle width (车同轨) mandated that the distance between the wheels on all vehicles be set at six Chinese feet, ensuring uniformity.

You might wonder why this mattered or how they could enforce this rule.

People might think that standardizing axle widths was unimportant; just another way for the central authority to assert its control. But when you dig deeper, it’s clear that it was far more significant.

This reform was nothing short of a revolutionary breakthrough in ancient transportation.

To understand why, let’s look at the roads back then. What kind of roads were they?

The answer: dirt tracks.

In fact, even today, in many rural areas in China, roads are still made of dirt, and heavy vehicles often damage them, especially when they become muddy.

Here are the next questions: why do these vehicles cause damage? When does the most damage occur, and when are deep tire ruts created?

The answer: on rainy days.

After it rains, dirt turns to mud, making it difficult to travel and causing deep ruts to form. This is why we often see tire tracks left by trucks on muddy roads.

Most dirt roads are passable for modern vehicles, regardless of conditions, but in the past, travel was much more challenging.

Unlike today, with wheels made of rubber, ancient wheels were made of wood. Even modern rubber tires can get stuck in the mud, so imagine how much worse it was when the wheels were wooden.

Traveling on established wheel ruts kept carriages steady, significantly reducing the strain on animals and the wear on axles—much like how geese flying in a V formation conserve energy.

It’s not that vehicles couldn’t travel on roads without ruts, but doing so was slower, more damaging to the carts, and more costly overall.

In narrow pathways with ruts that could only fit one vehicle, if two carriages met head-on, it would be quite a hassle. Both drivers would have to decide which one should yield and move out of the rut.

And throughout history, these situations often led to arguments.

Why the fuss, you might ask?

Well, yielding the rut was no easy task.

First, the driver had to whip their oxen or horses to haul the cart out of the deep rut and let the other one pass. Then, they had to get the wheels back into the rut to continue forward.

This was exhausting!

Now we understand the significance of wheel ruts on ancient roads, we can see why Qin Shi Huang unified the axle width across the country.

When axle widths were standardized nationwide, it meant that all the ruts formed by wheels were exactly the same size: six Chinese feet wide.

This allowed carriages to move freely across the country, similar to a modern railway system!

Imagine traveling from Zhao State to Hebei, only to be told by the driver, “You’ll need to change carriages here; the road ahead is incompatible.” Then, after changing carriages and reaching Qi in Shandong, the driver tells you again, “Switch carriages—the ruts won’t match up ahead.”

How could a country be managed as one unified system under such conditions?

From a smaller perspective, mismatched wheel ruts would make travel inconvenient.

From a broader perspective, the size of ruts directly impacted the state’s ability to transport resources and conduct business.

If you needed to transport a million piculs of grain to the front lines and each province used a different axle width, where would you find enough carriages of each type? By the time you gathered them, the soldiers would have starved.

Wheel ruts remained significant, even into the last century. Only after rubber was invented for tire production did traditional iron-rimmed wooden wheels start to phase out. Rubber tires reduced wear on roads, making traditional ruts less important.

Building on the uniform axle width, Qin Shi Huang ordered the construction of express roads radiating from Xianyang to other parts of the country—an engineering marvel.

This infrastructure allowed the Qin Dynasty’s influence to stretch east to Yan and Qi, and south to Wu and Chu. It facilitated a massive leap forward in strategic reach, enabling them to deploy forces anywhere in the empire with pinpoint precision, quickly and decisively.

The power of transportation has long been recognized. When the Eight-Nation Alliance invaded, they tore down city walls and built railways directly to the Legation Quarter in Beijing.

Why was this such a priority?

Because railways are the modern equivalent of wheel ruts.

After the Normandy landings, railways were promptly constructed to enable follow-up troops to advance—following the same principle.

Where the road extends, so does your strategic reach, and Qin Shi Huang understood this.

However, understanding it was the easy part; implementing it was incredibly challenging.

Research shows the express roads built by the Qin Dynasty stretched over 6,800 kilometers. These were not simply the dirt tracks we discussed earlier.

China’s varied terrain meant they had to adapt the construction methods. For example, when building roads to Sichuan, they had to make plank roads—wooden paths supported by posts over cliffs and ravines. In the south, they built stone bridges across countless waterways.

One can only imagine the immense dedication and labor that China’s ancestors put into these projects.

Thanks to these efforts, Ying Zheng could summon the manpower of the entire nation to serve him.

By standardizing axle width, Qin Shi Huang took a critical second step in integrating the six conquered states through transportation.

Qin Shi Huang’s third step was to unify weights and measures.

Many people might wonder: wasn’t it more important to unify currency rather than weights and measures? Currency might seem like the foundation of an economy, so logically, wouldn’t unifying it across the six former states be the highest priority?

Let’s consider it in practical terms, using grain as an example.

At that time, currency wasn’t always practical. When it came to large-scale transactions, it wasn’t feasible to transport massive quantities of grain back and forth, given the high costs of transportation.

But Qin Shi Huang did unify currency. He was far too meticulous to overlook something like that.

However, this reform came a bit later, closer to the end of his life. On the other hand, standardizing weights and measures was an effort he didn’t delay at all.

So, why was unifying weights and measures so essential?

At that time, weights and measures were more important than currency.

In small daily transactions, grain could serve as a medium of exchange; it was only in larger transactions that the need for currency arose.

The economy at the time was far from fully developed, so currency wasn’t urgently needed. However, grain was critical for national taxation.

Currency only has a consistent value when weights and measures are unified.

Here’s a relatable example: on the mainland, one jin (a traditional unit of weight) is ten taels, while in Taiwan, one jin equals sixteen taels. So, when mainland Chinese tourists go to Taiwan, they often feel like Taiwanese vendors are being extra generous. On the other hand, when Taiwanese tourists come to the mainland, they think the vendors are stingy.

This issue arises because the two regions have different weight standards for a jin.

Such differences can create deep emotional reactions. Taiwanese tourists spend Chinese Yuan exchanged from New Taiwan dollars, which are subject to an exchange rate. As a result, they may not be sensitive to price differences.

But they won’t necessarily remember that “a mainland jin” weighs less and therefore may be slightly cheaper. Instead, they might feel shortchanged!

This seemingly minor issue can grow into something more significant as it affects people’s sentiments. Good experiences are often forgotten or overlooked, but bad experiences tend to be remembered and can have a lasting impact.

It’s simply human nature!

Similarly, the lack of standardized weights and measures not only made tax collection for the Qin Dynasty far more difficult but also affected public sentiment and loyalty.

At that time, taxes weren’t paid in money but rather in grain. This created a major obstacle between the government and the people.

An official sent to Chu might measure tax in pots, while an official in Yan could be using sacks to calculate it.

This inconsistency made taxes hard to calculate and collect, and left room for corrupt officials to exploit the system: “You didn’t bring enough; your dou is only worth a bowl by my measure. Go home and bring more.” A dou was a traditional unit of volume in ancient China, commonly used to measure grains and other dry goods. One dou is approximately equal to 10 liters in modern measurements, though the exact volume varies depending on the historical period.

People, frustrated by these unequal measures and confusing conversions, would channel all their anger toward the state as a whole.

They would say, “Qin is unjust,” not “Qin’s officials are unjust.”

The lack of unified weights and measures raised tax costs for both the government and the people.

If writing was the foundation of the bureaucratic system, standardized weights and measures became its fundamental tool.

Without unified weights and measures, tax collection would be chaotic, and it would be impossible to evaluate officials’ performance, track their work, or even pay their wages.

In ancient times, officials were initially paid in grain; even later on when currency or other goods were used, wages were still calculated based on a grain standard.

But what was the most crucial concept within the official system?

Rank.

With standardized weights and measures, Qin Shi Huang could start to grasp the complete picture of his empire.

He could calculate exactly how much land there was, how much grain it could produce, and how many people those resources could support. These figures turned into complex but solvable calculations.

It was no wonder that he soon began commissioning massive and awe-inspiring projects.

Standardizing weights and measures was essentially a grand financial reform.

From then on, taxes were collected consistently, whether in Xianyang, Liaodong, Sichuan, or Wu. The state gained clear insight into its resources, and people could rest assured, no longer fearing excessive exploitation.

Of course, exploitation still existed, but it now fell more on the officials than the state.

Since the state’s tax rates were set and consistent nationwide, any additional burdens could be seen as the work of corrupt officials.

The deeper implications of standardized weights and measures for the state’s authority are also worth considering.

The pen provided direction for the empire, while the scales brought clarity to its resources. Weights and measures complemented written language; without either, the state couldn’t function.

By standardizing weights and measures, Qin Shi Huang completed his third step in integrating the six states.

The reason Qin Shi Huang’s three reforms (language, axle width, weights and measures) worked so well was that they shared a common thread: simplification.

This provides an important lesson: reasonable simplicity is always impactful.

Simplifying complex issues is a major skill. Because not all simplifications are beneficial, the key lies in making them useful and practical.