The history of eunuchs actually dates back even further than that of emperors, with its origins tracing all the way to the era of slave societies. Slave owners, who controlled immense wealth and had numerous wives and concubines, needed someone to manage and serve their large harems of women.

To solve this problem, slave owners adopted a punishment known as castration—a practice that originated during the transition from patriarchal clan society to class society—and applied it to male servants in the palace. These castrated men were responsible for managing and serving the concubines and palace maids, thus giving rise to eunuchs. At that time, the feudal system hadn’t yet been established, so there were no emperors. Various terms were used to describe eunuchs, some highlighting their “purity” and lack of privacy, while others carried more insulting connotations.

Eunuchs, Imperial Concubines and Empress Dowager Cixi

In the Qing Dynasty, eunuchs were respectfully called “gong gong(公公)” in the palace and officialdom, while common folk referred to them as “lao gong(老宫),” though this was a term eunuchs disliked. Among themselves, they would call each other “ye(爷)” (lord) if they were of the same rank, and those of a lower rank would address higher-ranking eunuchs as “master.” However, they preferred to be addressed as “lao ye(老爷)” (sir).

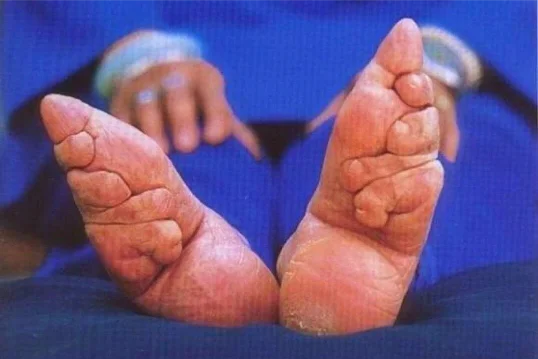

So, how did one become a eunuch? It began with the dreaded punishment of castration, which was a surgical procedure that rendered men incapable of performing sexually.

In fact, there was once a dynasty where all officials, both civil and military, were eunuchs, except for the emperor himself. To become a eunuch in the palace, one had to undergo castration first. By the Ming and Qing Dynasties, the law prohibited self-castration, with violators facing the death penalty. This wasn’t only due to the high mortality rate of self-castration, but also because the eunuchs of the Ming Dynasty had gained too much power, and the law sought to prevent individuals from changing their social or political status through such means.

The Qing Dynasty followed the old system of the Ming palace. However, some impoverished families, driven by desperation, secretly had their sons castrated because the official process was costly, requiring six taels of silver. Apart from those cases, most castrations were carried out by government-approved “knife workers”. For those aspiring to become eunuchs, surgery was the most challenging part, often a matter of life or death. Before the procedure, the knife worker and the child’s parents or guardian had to sign a document—a sort of liability waiver—stating that the procedure was voluntary and absolving the knife worker of responsibility in case of complications.

As for the removed genitalia, commonly referred to as “treasures,” they were first placed in a basin of lime powder to prevent decay and to absorb the blood and fluids. The organ was then cleaned with a wet cloth or handed back to the eunuch-in-training, who would soak it in sesame oil for several days. Once thoroughly soaked, it was placed in a small wooden box lined with silk, sealed, and stored for safekeeping.

There were two main methods for storage. One involved choosing an auspicious day to place the treasure above the central beam of the family’s ancestral hall. The other involved the knife worker treating it and placing it in a square container, storing it on a sealed high shelf. Both methods were known as “high ascension,” symbolizing the eunuch’s rise to prominence and success, along with good fortune. When it was time to retrieve the treasure, those with higher status would hold a careful ceremony, while poorer eunuchs would simply keep their treasure with them.

Aside from forced castration, there was an even more insidious method. When parents decided that their son would grow up to become a eunuch, they would entrust him to a special wet nurse skilled in a particular procedure. Over time, she would gradually damage his reproductive organs. As the boy grew older, he would show female characteristics, such as the absence of an Adam’s apple, rounded hips, and a high-pitched voice, effectively appearing more feminine. This was the path to becoming a eunuch.

Although eunuchs lacked physical desires, the emotional fire within them only grew stronger, and the palace maids who worked alongside them were often stunning beauties, handpicked from many. How could eunuchs possibly resist? In the vast, secluded palace, the only “real man” was the emperor. Even if the emperor worked himself to death, he still wouldn’t be able to satisfy all the women in the palace. Thus, loneliness became a constant theme for the palace maids. Where there is a need, a market arises.

Palace Maids with two little Palace Maids

This is how the strange phenomenon known as “duishi” (对食) came into being. Literally translated, duishi means “eating together,” but it came to refer to eunuchs and palace maids pairing up as temporary companions to ease their loneliness in the isolated palace.

However, what is lesser known is that the term duishi originally referred to lesbian relationships. As early as the Han Dynasty, palace maids, driven by loneliness, would comfort each other, euphemistically referred to as “mirror polishing” or “tofu grinding.”

The practice of heterosexual duishi flourished in the Ming Dynasty’s imperial palace. Living in solitude, unable to express their emotions, eunuchs and palace maids gradually became each other’s support. At that time, a palace would have tens of thousands of eunuchs and thousands of palace maids. Initially, it was the eunuchs managing the rooms who had the most contact with the palace maids, and over time, romantic feelings developed, leading to partnerships.

Another important reason was that during the Ming Dynasty, there was no dedicated kitchen for feeding the eunuchs. Until reforms at the end of the Ming period, eunuchs could only heat up cold food using charcoal. Palace maids, on the other hand, had small kitchens where they could cook their own meals, with sufficient supplies of ingredients and seasonings. Given this situation, many eunuchs courted palace maids, forming duishi relationships which allowed them to leave communal meals behind and enjoy the fine food prepared by the palace maids. For the eunuchs, this satisfaction of appetite was a major temptation.

Later, the eunuchs who helped palace maids procure clothing, food, and jewelry began actively pursuing them, showering them with attention. If a palace maid reciprocated and agreed to be with a eunuch, their relationship was referred to as a “caihu” (菜户). The term “caihu,” which originated in the Ming Dynasty, literally means “cook,” but it also implied a deeper relationship where the eunuch and palace maid would cook and eat together.

Relationships began with duishi, where couples ate face-to-face. Next, with caihu, they cooked and ate together—an upgrade, so to speak. At the caihu stage, the relationship became akin to a long-term partnership, almost like marriage. At this point, infidelity was not tolerated.

Historical records state that palace women without children would each choose a eunuch as their partner. Their finances were shared as if they were a family, and they loved each other like husband and wife. This practice later spread to include women who were lower ranked than concubines. Even if the emperor was aware of this, he would not forcibly prohibit it. As eunuchs had no sexual ability, there was no need for concern.

What’s the difference between duishi and caihu?

Aside from the terminology, the two had different meanings. Duishi was usually temporary and could occur between eunuchs and palace maids or even among women themselves.

On the other hand, caihu was openly allowed in the Ming court and permitted eunuchs to “marry” palace maids or form a lasting relationship. Eunuchs who became caihu with palace maids were devoted to their partners, working hard and being entirely obedient.

Initially, some eunuchs who weren’t involved in caihu mocked these eunuchs as spineless, envious of their relationships. However, over time, they realized the benefits of being with palace maids, and they too sought to become caihu.

Eunuchs would even swear oaths under the moon, vowing to love their partner for life and never engage in relationships with others. If a eunuch discovered that his beloved palace maid had shifted her affections, he would be devastated. However, eunuchs typically wouldn’t take revenge on the palace maid; rather, they would have sharp conflicts with her lover.

One example involved the wet nurse of Emperor Tianqi, Madam Ke, who first formed a duishi relationship with the eunuch Wei Chao. Later, she became involved with another powerful eunuch, Wei Zhongxian. The two men, jealous of each other, ended up fighting outside the Qianqing Palace, causing a scene that even alerted the emperor.

In addition to emotional support and companionship, eunuchs and palace maids also engaged in more intimate behaviors. According to the Qing Dynasty book “Renhai Ji”, during the reign of the Chongzhen Emperor, his favored concubine Imperial Noble Consort Tian exploited the promiscuity between eunuchs and palace maids to undermine her rivals. Imperial Noble Consort Tian would deliberately have palace maids carry her sedan chair into court, making the emperor wonder where the eunuchs had gone.

Imperial Noble Consort Tian seized the opportunity to complain about the behavior of the eunuchs, especially those in Empress Zhou’s palace, accusing them of engaging in inappropriate behavior with palace maids. She expressed her disgust to the emperor, who was infuriated and immediately ordered a search. The search uncovered many “toys” in the eunuchs’ and palace maids’ quarters. Just as the emperor was about to punish them, an older maid whispered that this was nothing unusual, suggesting that Imperial Noble Consort Tian’s palace might have even more. The emperor didn’t believe it at first, but after ordering a search of Imperial Noble Consort Tian’s quarters, they found even more bizarre and obscene toys to satisfy every imaginable fantasy.

At the heart of these phenomena were basic, unmet desires and emotions, representing the tragic loneliness of the individuals. According to one account, in the deep confines of the Ming palace, eunuchs and palace maids would carefully select their duishi partners. Once chosen, they would stay together for life, living like husband and wife, and taking pride in their loyalty to each other. If one of them died, the other would remain faithful and not seek another partner. Perhaps these glimmers of humanity are the shining moments in the vast river of history that deserve our attention.