I believe many of you are curious about a day in the life of a Chinese emperor. This article will detail a typical day for an emperor based on historical records from ancient documents, combined with some stories. After reading, you’ll understand that although emperors had supreme power and enjoyed wealth and luxury, they also bore immense responsibilities. They were not only symbols of the nation but also had to manage political, military, and economic affairs. If they ruled well, they would be remembered for generations; if not, they would be condemned through history.

Now, let’s dive into the topic:

Table of Contents

- 4:00 AM: Greetings at the Palace of Compassion and Tranquility

- 5:00 AM – 7:00 AM: Morning Meal and Early Lessons

- 7:00 AM – 9:00 AM: Holding Court at the Gate of Heavenly Purity

- 9:00 AM – 11:00 AM: Reviewing Memorials to the Throne and Making Comments on It

- 11:00 AM – 1:00 PM: Emperor’s Daily Lessons

- 2:00 PM: Emperor’s Dinner

- 3:00 PM – 5:00 PM: Emperor conducts Imperial Summons and Introductions

- 5:00 PM – 7:00 PM: Enjoy Opera Performances

- 7:00 PM – 9:00 PM: Enjoy His Treasured Artworks

- Flip The Plaques

4:00 AM: Greetings at the Palace of Compassion and Tranquility

Emperor Kangxi / Image Source: Wikipedia

Let’s take a look at what the Kangxi Emperor did after waking up. He resided in the Palace of Heavenly Purity (Qianqing Palace) and would start his day by washing up and having a light breakfast, usually a bowl of bird’s nest soup sweetened with rock sugar. After that, he would board a sedan chair, either carried by four or eight people and head to the Palace of Compassion and Tranquility to pay his respects to his grandmother, Grand Empress Dowager Xiaozhuangwen, who was the most prominent empress dowager residing in the Palace of Compassion and Tranquility. Every day, Kangxi would walk into the palace on foot and kneel before her to express his filial piety. Empress Dowager Xiaohuizhang, Kangxi’s stepmother after his biological mother passed away, also lived in the palace.

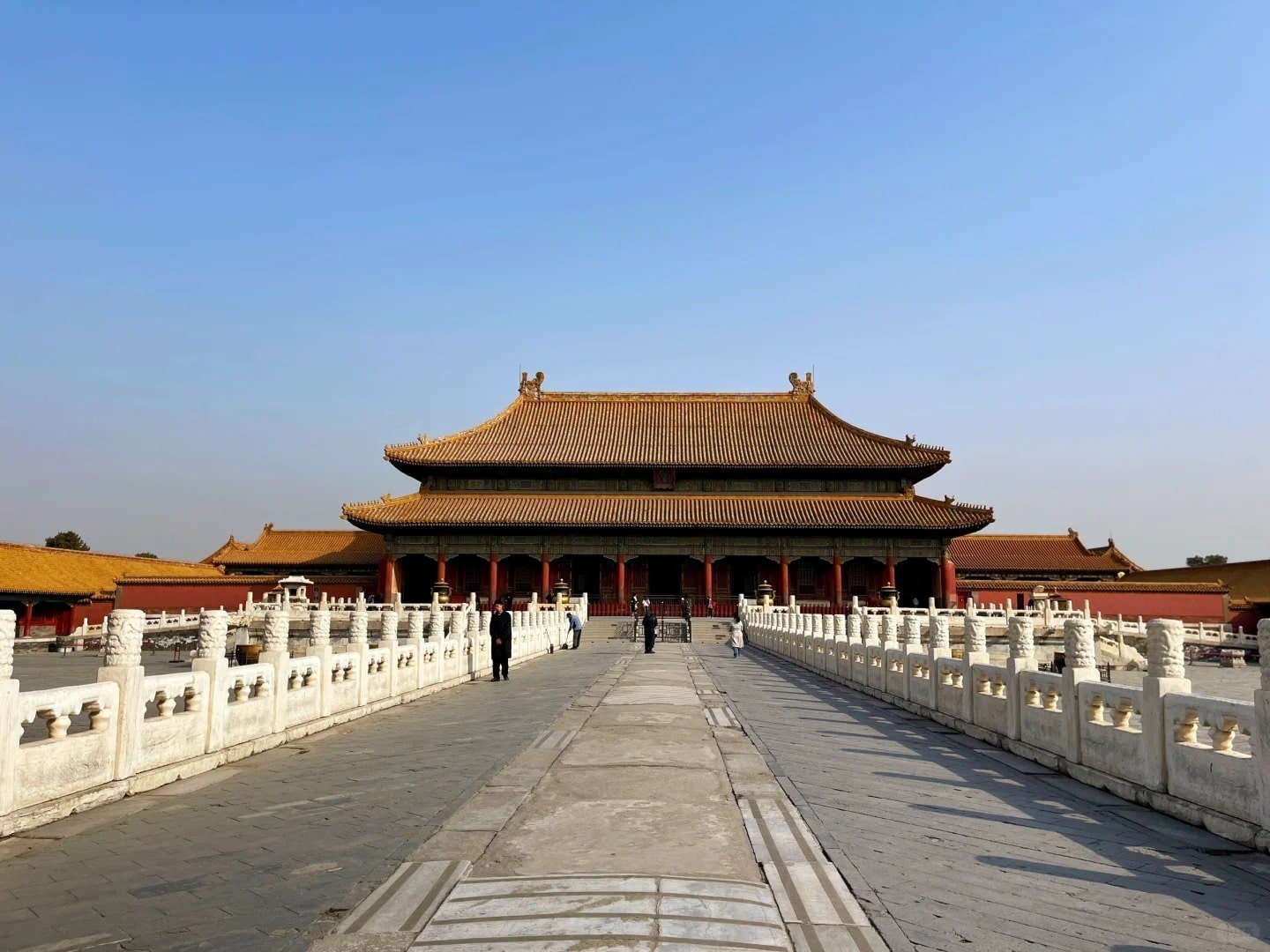

The Palace of Heavenly Purity (Qianqing Palace)

Kangxi’s relationship with his grandmother was exceptionally close, as she had raised him after the death of his father, Emperor Shunzhi when Kangxi was eight and the subsequent death of his biological mother when he was nine. This close bond was forged as Grand Empress Dowager Xiaozhuangwen took on the responsibility of raising Kangxi during a very turbulent time in his life.

Grand Empress Dowager Xiaozhuangwen / Image Source: Wikipedia

Despite the close bond between Kangxi and his grandmother, Xiaozhuangwen’s relationship with her son, Emperor Shunzhi, was not as strong. Although Shunzhi was devoted to his mother, as evidenced by his efforts to renovate the Palace of Compassion and Tranquility for her and by writing thirty birthday poems for her fiftieth birthday, their relationship was strained due to Shunzhi’s dislike of the empress chosen for him by his mother. His decision to depose his first empress and his obsession with his favorite consort, Consort Donggo, further alienated him from Xiaozhuangwen, especially after Consort Donggo’s death, which led Shunzhi to contemplate becoming a monk. This, of course, displeased Xiaozhuangwen.

Emperor Shunzhi / Image Source: Wikipedia

In contrast, Kangxi’s relationship with his grandmother was very good, as she had almost single-handedly raised him. He suffered from smallpox as a child and was temporarily moved out of the palace to recover. Upon his return, his father passed away shortly after, and four months later, his mother also died. Thus, Kangxi was left in the care of his grandmother, who nurtured him. Every morning, Kangxi would go to the Palace of Compassion and Tranquility to greet her, sometimes immediately after waking up and sometimes after attending the morning court.

The morning court sessions were held at the Gate of Heavenly Purity, which was conveniently close to the Palace of Compassion and Tranquility. After court, Kangxi would visit his grandmother again to pay his respects, making it a daily routine to visit her twice, both in the morning and in the afternoon. When the Grand Empress Dowager Xiaozhuangwen travelled outside the palace, Kangxi would accompany her, walking alongside her sedan chair through the palace until they reached the Gate of Divine Prowess, after which he would mount his horse. On dangerous parts of the journey, Kangxi would dismount and walk beside his grandmother’s sedan until it was safe to ride again. In the evening, he would wait until her sedan was settled and she had begun her meal before he would eat.

Gate of Heavenly Purity

Gate of Divine Prowess

In her later years, Grand Empress Dowager Xiaozhuangwen suffered from a skin condition, and the busy Kangxi would still accompany her six times to the hot springs for treatment, each time staying with her for several weeks. When she became gravely ill, Kangxi did not change his clothes or leave her side for days, attending to her every need. He would provide her with food and medicine, ensuring that anything she desired was immediately brought. During one of the coldest winters, on the first day of the twelfth lunar month, Kangxi walked ten miles from the Forbidden City to the Temple of Heaven to pray for his grandmother’s health, offering to shorten his own life in exchange for hers. Despite his prayers, Grand Empress Dowager Xiaozhuangwen passed away on the twenty-fifth day of the twelfth lunar month, just days before the Lunar New Year.

Devastated by her death, Kangxi considered canceling the New Year celebrations but eventually returned to the Palace of Heavenly Purity on the first day of the new year to observe a mourning period. He initially planned to mourn for twenty-seven months but shortened it to twenty-seven days due to pressure from his ministers. After Xiaozhuangwen’s death, Kangxi transferred his filial devotion to Empress Dowager Xiaohuizhang. He built the Palace of Tranquil Longevity for her as a replacement for the Palace of Compassion and Tranquility, which had become too emotionally charged after Xiaozhuangwen’s passing.

When leaving the Forbidden City for a journey, Kangxi would still send a report to the Empress Dowager at least once every three days to inquire about her well-being, along with various gifts. Kangxi sent a particularly touching birthday card to the Empress Dowager from the frontier. In the card, he wrote: “Today is an auspicious day in October, a time of celebration. Yet, I am far away, beyond a thousand mountains, and cannot raise a cup in your honor. My heart is filled with anxiety and deep longing (he wants to go back asap to see and bless Empress Dowager), so I send you my most sincere wishes from afar.” He also ensured that the yearly allowance and gifts were delivered to her through the Crown Prince, expressing his only wish that the Empress Dowager enjoy eternal longevity and shine with the years. The Crown Prince later informed him that the Empress Dowager had received the gifts, and upon reading his letter, she was moved to tears. However, she only accepted the gifts and refused the silver. Kangxi then wrote to the Crown Prince again, urging him to persuade his grandmother, explaining that the silver was a fixed part of her annual allowance, necessary for the many people she needed to reward and that she should certainly accept it.

Kangxi often reflected on how he had served the Empress Dowager for over fifty years. He recounted the many milestone birthdays she celebrated in the Palace of Tranquil Longevity, including her 50th, 60th, and 70th birthday celebrations. On the occasion of her 70th birthday, when Kangxi was already 57 years old, he personally led his sons and grandsons in a celebratory dance to honor her, joining them in a collective performance. This act of devotion and filial piety truly demonstrated the depth of Kangxi’s affection and respect for his mother.

Empress Dowager Xiaohuizhang / Image Source: Wikipedia

5:00 AM – 7:00 AM: Morning Meal and Early Lessons

The emperor would have breakfast from 5:00 to 7:00 AM and attend his morning lessons. The emperors of the Qing Dynasty typically only had two main meals a day: breakfast, which was usually around 6:00 AM, and dinner, which was around 2:00 PM. Since the Manchus ruled the Qing Dynasty, they followed Manchu dietary customs. The emperor’s breakfast usually consisted of about twenty different dishes, along with dozens of types of pastries. However, the emperors of the Qing Dynasty did not eat beef out of respect for agriculture, as cattle were essential for plowing fields. Instead, they had a preference for tofu and other soy-based foods.

Before or after breakfast, the emperor would attend his morning lessons. These lessons often involved reading from the “Veritable Records” or the “Imperial Edicts.” The “Veritable Records” in the imperial palace refers to the officially compiled historical records of an emperor’s reign. These records meticulously document the emperor’s daily governmental activities, major decisions, court affairs, diplomatic matters, and significant events. The “Veritable Records” was compiled by designated historians who used various archives, memorials, and court session records to ensure a comprehensive and accurate account of the emperor’s rule.

The “Veritable Records” was usually compiled after the emperor’s death by the imperial court, serving as an official historical document with significant historical value. These records not only provide later generations with first-hand information about the history of that period but also offer lessons and insights for future emperors and officials.

Meanwhile, the “Imperial Edicts” refer to the emperor’s words, teachings, or instructions. These typically include the emperor’s guidance or directives on matters such as governing the state, managing affairs of the state, and moral cultivation. “Imperial Edicts” could be teachings directed at ministers, members of the imperial harem, or offspring in the emperor’s daily life or important speeches delivered on special occasions.

“Imperial Edicts” were often recorded and might be compiled into books, such as the “Record of Imperial Instructions,” for future reference and study. In feudal society, these instructions were regarded as possessing extremely high authority and moral influence, and the populace was expected to study and adhere to them diligently. For later emperors and officials, the “Imperial Edicts” of their predecessors were also important materials to learn from, helping them understand the principles of governance and statecraft.

The Qing Dynasty had twelve emperors in total, and with the exception of Guangxu and Puyi, each emperor had his own “Imperial Edicts.”

The “Imperial Edicts” sometimes mentioned matters related to food. For instance, Emperor Yongzheng, who was the son of Kangxi and the father of Qianlong, was known for his frugality. He issued two specific edicts to avoid food waste. The first order was that any leftover food should not be thrown away. Instead, it should be given to servants and soldiers or even fed to cats and dogs. If the animals wouldn’t eat it, the leftovers should be dried and used to feed birds. In short, no food was to be wasted. Three years later, he issued another edict emphasizing that the grains given by heaven were meant to sustain life and that not a single grain should be discarded lightly. When cooking rice, it was better to prepare a little less rather than waste any. If any leftovers were found, the eunuchs and supervisors were required to collect them, and anyone caught discarding food would be punished with forty lashes.

Emperor Yongzheng / Image Source: Wikipedia

The Qing emperors were generally not extravagant in their meals, with the most extravagant being the Empress Dowager Cixi. She had over a hundred chefs at her service and fifty eunuchs just to bring her meals. One of her dishes was called “Vinegar-Stewed Sprouts,” which involved stuffing meat into bean sprouts, an incredibly complex dish to prepare. In contrast, the most frugal emperor was Daoguang, who limited himself to just five dishes per meal—four side dishes and one staple.

Empress Dowager Cixi / Image Source: Wikipedia

As for Kangxi, his meals were simple but focused. He would often have just one type of dish per meal—either lamb or pork, but not both.

7:00 AM – 9:00 AM: Holding Court at the Gate of Heavenly Purity

From 7:00 to 9:00 in the morning, the emperor would hold court at the Gate of Heavenly Purity, listening to state reports. Why did the Qing emperors hold court at the Gate of Heavenly Purity instead of the Hall of Supreme Harmony, as emperors of previous dynasties had done? The reason was that the Hall of Supreme Harmony was too far away. The emperor would have to traverse a large portion of the Forbidden City just to begin his workday. The Qing emperors decided to save themselves some effort and moved the location to the Gate of Heavenly Purity. But why did the emperor hold court at a gate rather than in a hall? One theory suggests that it was due to the precedent set by Emperor Yongle of the Ming dynasty, Zhu Di, who built the Forbidden City. Three months after its completion, the three main halls were destroyed by fire, so meetings had to be held at the Gate of Supreme Harmony instead. This practice of court at the gate was then passed down through the generations.

Hall of Supreme Harmony

Three days each month—on the 5th, 15th, and 25th—the Kangxi Emperor would hold court in the Hall of Supreme Harmony, where he met with envoys from vassal states and foreign diplomats. Smaller meetings with ministers were held in the Palace of Heavenly Purity or the Hall of Mental Cultivation. Thus, the regular daily meetings took place at the Gate of Heavenly Purity once each day. The Kangxi Emperor valued collective wisdom, and this practice of court at the gate continued for more than fifty years.

How did they hold meetings at the gate?

In fact, the grand gates within the Forbidden City were not just ordinary doors. For instance, the Gate of Heaven-Sent Peace and Meridian Gate are actually gate towers. Gates like the Hall of Supreme Harmony Gate and the Gate of Heavenly Purity are more akin to entrance halls and can be seen as the emperor’s reception rooms. The distance from the Palace of Heavenly Purity to the Gate of Heavenly Purity was convenient for the Kangxi Emperor, being only a little over eighty meters. However, ministers had to travel far distances to attend these meetings. For the 7:15 AM meeting, they had to gather at the Meridian Gate by 5:00 AM, which meant they had to wake up in the middle of the night to wash and get ready. Military officials would ride horses, while civil officials would travel in sedan chairs or carriages. On the way, officials had to memorize the documents, committing the reports to memory to avoid being scolded during the meeting.

Gate of Heaven-Sent Peace

Meridian Gate

These meetings were held daily, which became exhausting for the officials.

Some eventually submitted petitions, asking, “Your Majesty, we have to wake up in the middle of the night every day, and this constant fatigue is affecting our ability to handle daily affairs. Could we alternate between Manchu and Han officials for court sessions, with different ministries attending on different days?”

To this, Kangxi replied, “No.”

Another official then suggested, “Your Majesty, could we hold court once every five days or at least every two or three days?”

Again, Kangxi said, “No.”

After another two years, an official proposed that on the days when the emperor held court in the Hall of Supreme Harmony, they could skip the gate meetings. He also suggested reducing the number of meetings during extreme cold or heat.

Kangxi responded, “Let’s do this: documents can be submitted to the Grand Council first. If there’s heavy rain or snow and no urgent reports to review, we can take a day off.”

These daily gate meetings were also a significant challenge for Kangxi, making him one of the most diligent emperors in history. He held court every day and attended to his duties without fail.

By the Yongzheng period, the frequency of these meetings had greatly decreased, occurring three or four times a month.

During the Qianlong period, the meetings were held less than twice a month.

By the Daoguang period, it had dwindled to once every two months.

During Emperor Xianfeng’s reign, the practice of court at the gate was finally abolished, with the last meeting taking place in the ninth year of his reign.

The reduction in these meetings did not necessarily mean the emperors were less diligent. For example, Emperor Yongzheng, who was just as diligent as his father, Kangxi, managed the state by reviewing documents late into the night, demonstrating that attending to state affairs could take different forms.

9:00 AM – 11:00 AM: Reviewing Memorials to the Throne and Making Comments on It

From 9 AM to 11 AM, after finishing the morning court session (which doesn’t mean the emperor is done for the day), the Kangxi Emperor would begin his second task of the day: reviewing memorials to the throne and making comments in red ink. At 9:45 AM, the Kangxi Emperor would return to the Palace of Heavenly Purity, change out of his court robes into more casual attire, and start reading the reports. The court robes were the emperor’s work uniform, but at the Palace of Heavenly Purity, which was the emperor’s residence, he would naturally want to dress more comfortably. Most of the time, the emperor wore casual clothes.

The reports delivered to the emperor’s desk came in three types: Tiben (题本), Zouben (奏本), and Zouzhe – memorials to the throne (奏折).

What’s the difference between them?

Tiben are official reports sealed with an official stamp, Zouben are reports without an official seal, and Zouzhe – memorials to the throne are essentially private correspondence between the emperor and his officials. Tiben is the most cumbersome type of report, with a standard length of 300 characters, though it could be longer. It required a summary, not exceeding 100 characters, to be written on yellow paper and attached to the cover, which is called a “tiehuang” (贴黄). The font had to be in a fine style, not bold.

Zouben required Songti (宋体) script, and the report had to indicate the number of words and pages at the end.

Zouzhe was more like a free-form essay. The emperor stated that as long as the writing was neat, it could be somewhat cursive and large. However, the official writing of the Zouzhe had to be written by hand, without assistance, unless they had the emperor’s approval. This strict rule was because the Zouzhe – memorials to the throne were a private communication between the emperor and his officials, and the emperor personally responded in his own handwriting. If an official used a ghostwriter, it would be considered an insult to the emperor.

How were these documents delivered to the emperor?

Tiben, being an official report, was sent via a courier system similar to a postal service, going through multiple stations to reach the capital, then forwarded to various ministries, the cabinet, and finally to the emperor.

Zouzhe – memorials to the throne, being private letters, couldn’t use the courier system unless it was an urgent matter. Instead, officials had to send these letters directly to the imperial palace via their own servants or family members, either on horseback or by boat.

Zouzhe – memorials to the throne would arrive at the palace late at night, first being delivered to the Outer Palace Secretariat at Jingyun Gate at 2 AM, then to the Inner Palace Secretariat at Gate of Heavenly Purity by 3 AM. The Outer Palace Secretariat was outside the Gate of Heavenly Purity and the Inner Palace Secretariat was inside it.

During the night, only four people, including the emperor himself, were inside the Gate of Heavenly Purity: two imperial physicians and an official on duty at the Inner Palace Secretariat. For security reasons, there were eunuchs supervising the officials, who were not allowed to step down from the Inner Palace Secretariat’s footstep. The Inner Palace Secretariat was mostly staffed by eunuchs, but the official on duty was not a eunuch.

Zouzhe was delivered to the emperor in a special box that remained locked until the emperor personally unlocked it with his key. This confidentiality was critical. Each official who wrote Zouzhe would receive at least two of these locked boxes and up to eight. The official and the emperor each held a key.

Zouzhe was required to use one of three materials: yellow silk, yellow paper, or note paper. The content of the Zouzhe could be categorized into two types: Qing’an Zhe (请安折), which used yellow silk for the cover and yellow paper for the content, and non-Qing’an Zhe, which used note paper, typically white paper.

During the reign of Emperor Yongzheng, who was known for his frugality, he suggested that all Zouzhe be written on white paper to save costs. Not everyone had the privilege of writing Zouzhe to the emperor; during Kangxi’s reign, only institutions directly serving the emperor had this privilege.

Qing’an Zhe was written by ministers who were concerned about the emperor’s well-being and inquiring about his health. There’s an interesting story about an official named Li Xu (李煦) who wrote a Qing’an Zhe to Emperor Kangxi. The top half of the letter inquired about the emperor’s health, while the bottom half reported that the Jiangnan General had passed away due to an illness. Kangxi replied, “Matters of health should not be mixed with such grave news. This is highly disrespectful.”

Did the emperor get tired from reviewing so many Zouzhe every day? Not really, because the most common comment written by the emperor was “Acknowledged. However, there were emperors who took the task of reviewing memorials very seriously. Emperor Yongzheng was the most diligent; he rarely wrote “Acknowledged,” instead, he would often write dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of characters in response.

Being a person is hard, but being an emperor is even harder. This is what Emperor Kangxi said during a meeting in the East Warm Pavilion of The Palace of Heavenly Purity. He said, “I am 70 years old, with over 150 sons, grandsons, and great-grandsons. The country is stable, and we live in a time of relative prosperity. I’ve been busy for decades, and it’s far from easy.

Throughout history, emperors often had short lives, and historians tend to think it was due to indulgence in wine and women, but this is a scholar’s view. Their short lives were really due to the exhaustion from governing the empire.

Whenever I see an old minister’s retirement request, I’m moved to tears. You all get to retire eventually, but where can I retire? Emperor Kangxi once wrote in a Zouzhe: “Every red-ink comment of mine is written by my own hand, never by someone else. Even if my right hand is sick, I’ll use my left hand. I would never let someone else do it for me. So rest assured that whatever is in the Zouzhe is known only to the person who wrote it and myself, who reviewed it.”

When writing Zouzhe to the emperor, it must never be too long.

Here’s another funny and sad story: A military officer once wrote a Zouzhe that was over 5,900 characters long. Emperor Yongzheng responded, “How dare you have the audacity to write such a long letter?”

Being reprimanded by Yongzheng was relatively mild compared to what happened during the reign of the Hongwu Emperor, the founder of the Ming Dynasty.

An official from the Ministry of Justice, Ru Taisu, wrote an extremely lengthy report. The Hongwu Emperor had it read aloud to him. After listening to 6,000 characters without hearing any concrete suggestions, he summoned Ru Taisu and had him beaten. The next day, he had the report read again. After 16,500 characters, five specific suggestions were finally mentioned. The Hongwu Emperor then admonished Ru Taisu, “You could have made your points in 500 characters, but you wrote 17,000. You deserved the beating.”

Based on existing archives alone, Emperor Yongzheng, during his 13 years as emperor, reviewed 22,000 Zouzhe and 190,000 Tiben. He truly was a diligent emperor.

After attending court for two hours and reviewing reports for another two hours, was the emperor finally done for the day? What would he do next?

11:00 AM – 1:00 PM: Emperor’s Daily Lessons

From 11 AM to 1 PM: The Kangxi Emperor would attend lessons after the morning court session. His teachers would be waiting for him at the Hongde Hall, which was the most frequently used location for his daily lectures. These lessons were called Rijiang (日讲 – Daily lectures), and Kangxi had over ten teachers who took turns teaching him each day. Why did the emperor need to attend lessons? In Chinese cultural tradition, there is a custom called Jingyan (经筵 – Classic Lecture), where the emperor receives further education.

The “Jing” (经) in Jingyan broadly refers to classical cultural texts, specifically the Four Books and Five Classics. The Four Books are “The Great Learning” (《大学》), “The Doctrine of the Mean” (《中庸》), “The Analects” (《论语》), and “Mencius” (《孟子》). The Five Classics are “The Book of Songs – The Classic of Poetry ” (《诗经》), “The Book of Changes – I Ching” (《易经》), “The Book of Documents” (《尚书》), “The Book of Rites” (《礼记》), and “The Spring and Autumn Annals” (《春秋》).

The “Yan” (筵) in Jingyan means a lecture, so Jingyan refers to lectures on the classics given to the emperor. Attending Jingyan was a solemn ceremony, often involving hundreds or even thousands of participants.

Rijiang, on the other hand, was a more intimate setting where the emperor had face-to-face discussions with his teachers.

During the Qing Dynasty, Jingyan was typically held at the Hall of Preserving Harmony. During these sessions, the emperor would sit opposite his teachers, with two officials standing by his side to help him turn the pages of the texts: one on the east side for the Four Books and another on the west side for the Five Classics and historical texts.

Hall of Preserving Harmony

The first Jingyan session for Kangxi took place on the 17th day of the second lunar month in the 10th year of his reign. A month and a half later, his daily lessons began. Kangxi had 16 Jingyan officials and 10 Rijiang officials, with the added role of Imperial Chronicler (起居注官) for keeping daily records of the emperor’s words and actions.

The emperor’s daily lessons were initially held every other day, but Kangxi changed it to daily lessons because he found joy in learning and felt that every other day lessons were insufficient.

He said, “Apart from managing state affairs, my daily routine consists of studying and learning, which I never tire of. Learning should not be intermittent.” While this made the emperor happy, it greatly burdened his teachers, who requested more time to prepare, but Kangxi refused, insisting on the daily schedule. This meant that teaching the emperor required thorough preparation and detailed lecture notes.

Kangxi, always full of ideas, proposed changes to the Jingyan format, where traditionally, the teachers lectured while the emperor listened in silence. He suggested a more interactive approach, where after the teachers spoke, he would also present his understanding, and they would discuss and debate any unclear or questionable points. Eventually, Kangxi even decided to lecture first, followed by his teachers.

His passion for learning was so intense that even during the Revolt of the Three Feudatories. This conflict lasted eight years, and he continued with his daily lessons without interruption.

Traditionally, there were two Jingyan periods each year: from the 12th day of the second lunar month to the summer solstice in May and from the 12th day of the eighth lunar month to the winter solstice in October. These periods were like school terms, and during extreme summer or winter conditions, breaks were typically taken. However, Kangxi abolished these breaks, insisting that lessons continue without pause, even on his birthday, the Wanshou Festival. When officials suggested taking a week off for his birthday, he declined, stating that he was eager to finish his studies on The Book of Songs – The Classic of Poetry (《诗经》).

However, by the 25th year of Kangxi’s reign, he began to lose interest in his lessons. What happened? That year, The Hall of Literary Brilliance was completed, and the first Jingyan session was held there, followed by daily lessons.

Afterward, the Jingyan and Rijiang responsibilities were transferred to the crown prince, and Kangxi personally oversaw the compilation of the Crown Prince’s Grand Lectures and Crown Prince’s Daily Lectures, which were the protocols for the crown prince’s lessons.

Kangxi himself shifted his focus from traditional Chinese studies to Western subjects, including astronomy, geometry, anatomy, and Western music theory. He felt that he had mastered Chinese classics and history to the point where he could “graduate,” and his teachers agreed, acknowledging that his knowledge was indeed impressive.

2:00 PM: Emperor’s Dinner

At 2 PM, it’s time for the emperor’s dinner. After breakfast, two hours of listening to state affairs, two hours of reviewing memorials to the throne, and two hours of small group lessons, the emperor would then have a meal. Qing Dynasty emperors typically had two main meals: breakfast at 7 AM and dinner at 2 PM. However, they also had an early morning snack at 6 AM and a light evening meal at 6 PM, meaning the emperor actually ate four times a day. The emperor would never go hungry; he could always have additional snacks, especially desserts, whenever he wanted.

Emperor Qianlong particularly enjoyed a dessert called “Ba Zheng Gao” or “Ba Zheng Cake” (八蒸糕), which originally came from the Ming Dynasty. Qianlong modified the recipe by replacing hawthorn with ginseng. His version of the recipe included ginseng, poria (茯苓), Chinese yam (山药), hyacinth beans (扁豆), barley (薏米), gorgon fruit (芡米), polished round-grain rice (粳米粉), and glutinous rice flour (糯米粉), all ground very finely, mixed with white sugar and then steamed into a cake.

Every day when Qianlong drank tea, he would be served 4 to 6 pieces of Ba Zheng Gao – Ba Zheng Cake, without exception. In Chinese culture, there is a tradition of “food as medicine,” and Ba Zheng Gao – Ba Zheng Cake was considered both a delicacy and a health tonic.

How much tea was supplied to the emperor daily? Seventy-five packs, each weighing 100 grams, totaling 15 jin (about 9 kilograms). Of course, the emperor couldn’t drink all that by himself; most of it was used to reward officials in the outer court and concubines in the harem. Qianlong was very particular about the water used for brewing tea; he preferred spring water, specifically from Jade Spring Mountain (玉泉山) in the western suburbs of Beijing, as it had low mineral content. This preference was the opposite of his grandfather’s, who liked water with a high mineral content. Was there any water better than spring water? Yes, snow water was considered superior, and in the right season, Qianlong would use snow water to brew his tea.

Qianlong also drank milk tea daily, a habit inherited from the Manchu people, who were originally a nomadic tribe. How was milk tea made in the imperial palace? It was brewed using yellow tea from Zhejiang, which is a fermented tea. The milk tea in the Qing palace was made by simmering yellow tea with milk, cream, and salt.

Did the emperor eat Western food? During Qianlong’s reign, there is evidence that Western cuisine was indeed present. The emperor’s dining utensils included gilded copper spoons, golden spoons, ivory chopsticks, jade chopsticks inlaid with gold, and enamel bowls.

Emperor Qianlong / Image Source: Wikipedia

In addition to the meal list, there was also the Meal Card. The Meal Card didn’t list the names of dishes but rather the names of officials and nobles who sought an audience with the emperor. Nobles had red-topped cards, while ministers had green-topped cards. During the emperor’s evening meal, he would review the Meal Cards to decide who could be summoned or introduced to him next.

There is a saying about how the emperor ate: he could only take three bites of each dish. This is not entirely accurate. The rule stemmed from an ancient safety measure designed to prevent poisoning by disguising the emperor’s food preferences.

In ancient times, the emperor’s safety was paramount, so to avoid revealing the emperor’s favorite dishes, which could increase the risk of poisoning, a rule was established: “No more than three bites per dish.” This rule required the eunuchs serving the emperor to remove a dish after he had taken three bites, thereby reducing the likelihood of poisoning. While this rule existed and is documented in some historical sources, it was not absolute. Different dynasties and emperors had varying dining habits and rules.

3:00 PM – 5:00 PM: Emperor conducts Imperial Summons and Introductions

From 3 PM to 5 PM, the emperor would conduct Imperial Summons and introductions.

Let’s start with Imperial Summons. The emperor would usually summon some of the ministers from the Grand Council to the Hall of Mental Cultivation. Originally, during the Yongzheng Emperor’s reign, the Grand Council was primarily responsible for military affairs, but it later evolved into the emperor’s advisory body and secretariat. Over time, the Grand Council began to handle whatever matters the emperor assigned, meaning it became involved in almost all state affairs.

The ministers of the Grand Council had to be ready at all times to receive the emperor’s summons, listen to his verbal orders, return to the Grand Council to draft the edicts, and then bring them back to the emperor for approval.

The Grand Council was located less than 50 meters from the Hall of Mental Cultivation, making it very convenient for the emperor to summon them. It is said that the ministers of the Grand Council were summoned multiple times a day, having to run back and forth frequently. Often, the ministers were summoned collectively. A row of cushions was laid out in front of the emperor’s desk, and the ministers would kneel on them in sequence, spaced apart. The emperor would ask questions, and the minister being addressed would answer. No debate or interruption was allowed; otherwise, it would be considered a breach of decorum, for which one could be punished.

Now, let’s talk about Imperial introductions. This was a formal process where the emperor met with officials or guests, guided by senior officials into his presence. The officials being introduced typically had a longer route to take compared to those who were summoned directly. Introductions usually occurred in groups, with eunuchs from the Palace Secretariat relaying the messages.

During the Yongzheng Emperor’s reign, the introduction system became quite elaborate. Officials ranked below the fourth grade but above the seventh grade had to be introduced. For officials stationed in Beijing, those ranked below the third but above the eighth grade were introduced when appointed, transferred, or disciplined. Why did officials who were disciplined need to be introduced? The Yongzheng Emperor was concerned that some might have been wrongfully accused or unfairly treated by their superiors or disciplinary bodies, so he wanted to meet them personally.

During the Qianlong Emperor’s reign, the scope of introductions expanded further. In addition to newly appointed officials, even those already in office were frequently summoned for introductions. This included officials as low-ranking as county magistrates (知县) of the seventh and eighth grades and even low-ranking officials from the capital had the opportunity to be introduced to the emperor after passing examinations.

With so many officials to meet, how did the emperor keep track of them all? To the west of the Hall of Mental Cultivation was a building called the Hall of Diligent Government. On the west gate of the Hall of Diligent Government, a list was posted with the names of all officials ranked below governor-general but above prefect and below general but above brigade commander. The western wall displayed a roster of all official positions across the empire, with vacancies clearly marked, allowing the emperor to see everything at a glance.

Additionally, all officials being introduced had to submit an introduction card. Nobles had red-topped cards with vermilion heads, while officials had green-topped cards with their rank and name written in the middle. During his meal, the emperor would go through these cards to decide who would be granted an audience. The introduced officials were also required to submit an introduction form that detailed their personal history.

Throughout the year, the emperor would also meet with scholars. The Imperial Examination was still the most important pathway to advancement in the Qing Dynasty and was a system highly valued by the emperors.

To become a jinshi (进士), a scholar had to pass a series of examinations: the Tongshi (童试) for xiucai (秀才), the Xiangshi (乡试) for juren (举人), the Huishi (会试), and finally the Dianshi (殿试). The Tongsheng Examination (童生考试) was the test to become a xiucai. It consisted of three stages: the county examination (县试), the prefectural examination (府试), and the provincial examination (院试). The top-performing xiucai were eligible for a yearly stipend of four taels of silver.

The Xiangshi (乡试) was held every three years and was the test to become a juren. It was conducted over three rounds in August, each round lasting three days.

The Huishi was the national examination to become a jinshi, held in the second year after the Xiangshi. The Huishi was conducted in March, also over three rounds of three days each. After the Huishi, there was a re-examination, and those who passed were eligible for the Dianshi in April.

The Dianshi was originally held in October, but because of the cold, the Yongzheng Emperor issued an order to place more braziers inside the Hall of Supreme Harmony for warmth. By the fifth year of Yongzheng’s reign, the Dianshi had been moved to March, and by the end of Qianlong’s reign, it was further shifted to April.

The announcement of the results was still held at the Hall of Supreme Harmony, and the top three scholars, Zhuangyuan (the highest-ranking scholar in the imperial examination system in ancient China), Bangyan (the second-highest ranking scholar in the imperial examination system of ancient China), and Tanhua (third-highest ranking scholar in the imperial examination system of ancient China), had the honor of walking through the central gate of the Gate of Supreme Harmony and the Meridian Gate, exiting the Forbidden City in grand style. The emperor would naturally meet with the new jinshi since the Dianshi had no chief examiner; the emperor himself acted as the chief examiner.

In theory, all jinshi were considered students of the Son of Heaven (天子门生), so the emperor would personally introduce them. Juren, who didn’t pass the jinshi examination, usually wouldn’t get to meet the emperor, but the Yongzheng Emperor issued a decree allowing some of them to be selected as instructors or tutors.

Those selected had the opportunity to be introduced to the emperor before taking up their positions. Even xiucai, who didn’t pass the juren examination, had a chance. Gongsheng (贡生), who were top-performing xiucai selected for not passing the juren examination, could participate in the gongsheng examination for official positions (贡生考职).

During one such examination, the Yongzheng Emperor had the sudden idea to introduce and interview the candidates. Out of over 1,100 gongsheng candidates, about 900 didn’t dare to participate, but more than 200 did, and over 70 were granted official positions, demonstrating just how important these introductions were.

5:00 PM – 7:00 PM: Enjoy Opera Performances

From 5 PM to 7 PM, after a busy day, the emperor finally finished his duties. He would usually go to the Loft of Gentle Fragrance to enjoy opera performances. The stage at Loft of Gentle Fragrance was known for having the best acoustics in the Forbidden City.

In the rear hall of Loft of Gentle Fragrance, there was a small indoor stage called “Fengyacun” (风雅存), where Emperor Qianlong not only watched performances but also occasionally performed himself.

The stage at the Loft of Gentle Fragrance was the second largest in the Forbidden City; the largest was the stage at the Pavilion of Cheerful Melodies (畅音阁), located in the northeast corner of the Palace of Tranquil Longevity. The stage at Pavilion of Cheerful Melodies had three levels: the top was called Futai (福台), the middle was Lutai (禄台), and the bottom was Shoutai (寿台). These names—Fu (福), Lu (禄), and Shou (寿)—represented “blessing,” “wealth,” and “longevity,” respectively.

The emperor watched performances from the Yueshilou (阅是楼), a two-story building with five rooms on each floor. The Pavilion of Cheerful Melodies (畅音阁) was part of the Palace of Tranquil Longevity, which Emperor Qianlong expanded as a retreat for himself when he planned to become the retired emperor, so the stage at the Pavilion of Cheerful Melodies (畅音阁) was also prepared for his enjoyment.

Performances in the Forbidden City were, of course, held in high-quality theaters with excellent costumes. According to records from the Forbidden City, hundreds of plays were performed there, with top-notch costumes, props, and makeup. During the reign of Emperor Kangxi, there was even a time when real horses, tigers, and elephants were used in a performance.

When did performances typically take place in the palace, and what kind of plays were performed?

There were seasonal plays, celebratory plays, and birthday tribute plays. China has many traditional festivals, such as New Year’s Eve, New Year’s Day, Lantern Festival, Cold Food Festival, Dragon Boat Festival, Qixi Festival, Ghost Festival, Mid-Autumn Festival, Double Ninth Festival, Winter Solstice, Laba Festival, Buddha’s Bathing Festival, and Guan Di Festival (believed to be the birthday of Guan Yu).

Even when the emperor appreciated the lotus flowers, snow, or plum blossoms, performances would be held to celebrate.

Celebratory plays were staged for events such as the engagement or marriage of a prince, the birth of a young prince, the prince’s first bath, and the prince’s full-month celebration. When the emperor returned to the palace, went hunting, conferred a title on the empress dowager, or elevated a concubine’s rank, performances were also held. The empress dowager’s birthday, known as Wanshou Festival, the empress’s birthday, known as Qianqiu Festival (千秋节), and the emperor’s own birthday, which was the most important Wanshou Festival, was celebrated with grand performances, often lasting seven days—three days before and three days after the emperor’s birthday.

For Qianlong’s 70th birthday, the cost of hiring performers alone was 78,800 taels of silver. The most extravagant celebration was Qianlong’s 80th birthday, involving 6,300 performers. The famous British envoy Lord Macartney and his delegation visited China under the pretext of celebrating Qianlong’s birthday, seeking to establish trade relations. They had the opportunity to witness Chinese opera and were surprised to find that no women were playing female roles; all female characters were portrayed by men, indicating that by Qianlong’s time, male performers (known as nandan – male performers in female roles) had replaced female actresses.

When did the ban on women performing in the palace begin?

It is said that in the eighth year of Emperor Shunzhi’s reign, a decree was issued forbidding female performers from the Bureau of Music to enter the palace, and only eunuchs were allowed to perform. However, this decree was not fully enforced, as female performers continued to be present during the Kangxi era. Moving on to Emperor Yongzheng, he was rather peculiar. Although he witnessed the construction of the Qing Dynasty’s first three-story stage, Qingyinge (清音阁), and often invited opera troupes to perform when he was a prince after becoming emperor, he strictly prohibited officials from keeping opera troupes, declaring that any official with performers in their household was not a good official.

Emperor Jiaqing enjoyed organizing opera productions himself, acting as the director, and overseeing everything from casting to the timing of drums and gongs. Jiaqing was an opera enthusiast, and in his early reign, he watched operas for 18 days straight.

Emperor Jiaqing / Image Source: Wikipedia

The Hall of Mental Cultivation also served as a place for performances. After lunch, Emperor Daoguang often performed at the Hall of Mental Cultivation, even though it had no stage. These small performances, known as “Mao’erxi” (帽儿戏), involved minimal costume—actors might only wear boots and hats, with the red carpet serving as a stage. These modest performances were likely scorned by emperors who preferred grand spectacles, like Kangxi and Qianlong, but were common during the reigns of Jiaqing, Daoguang, and Xianfeng.

Emperor Daoguang / Image Source: Wikipedia

Xianfeng, another opera enthusiast, was watching a performance at his summer palace in Rehe just two days before his death. In his youth, Xianfeng liked to summon performers to the palace to teach eunuchs how to sing, and he would join in. Xianfeng also enjoyed writing lyrics, composing music, and playing the drums, a passion he shared with Qianlong.

Emperor Jiaqing / Image Source: Wikipedia

The last emperor known to enjoy drumming was Emperor Guangxu. After the Hundred Days’ Reform failed, Guangxu was imprisoned by Empress Dowager Cixi at Yingtai in Zhongnanhai. To relieve his worries, he would occasionally gather the eunuch opera troupe to accompany him in drumming and playing music.

Emperor Guangxu / Image Source: Wikipedia

Empress Dowager Cixi was a true opera enthusiast, and from her time onward, top performers from outside the palace began to work within the court. The best opera performances and performers can be seen in Forbidden City. The last opera performance in the Forbidden City took place on August 22, 1923.

7:00 PM – 9:00 PM: Enjoy His Treasured Artworks

From 7 PM to 9 PM, Emperor Qianlong would often visit the western room of Jingyixuan (静怡轩), known as “Si Meiju” (四美具), to appreciate his treasured artworks. “Si Meiju” was a place dedicated to storing and appreciating paintings, consisting of a storage room, an exhibition hall, and a secret chamber. The term “Si Meiju” originally referred to “Good Times, Beautiful Scenery, Pleasurable Things, and Joyful Events.” However, in this context, it also refers to Qianlong’s four most prized paintings: Gu Kaizhi’s (顾恺之) “Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies” (《女史箴图》), Li Gonglin’s (李公麟) “Dream Journey along the Xiao and Xiang Rivers” (《潇湘卧游图》), “The Shu River” (《蜀川胜概图》), and “The Nine Songs” (《九歌图》). Qianlong specifically set up this special room in Jingyixuan for this purpose.

Qianlong had an extensive collection of treasures, and there were many secret chambers to store them, such as “Room of Three Rare Treasures” (三希堂), Huachanshi (画禅室), Xueshitang (学诗堂), Sanyouxuan (三友轩), and Chun’ouzhai (春藕斋). Qianlong also enjoyed writing inscriptions and commentaries on these treasures.

What eventually happened to the “Four Paintings”? Today, only one, the “The Nine Songs,” remains in China, housed in the National Museum. “Dream Journey along the Xiao and Xiang Rivers” ended up in Japan, “The Shu River” is in the United States, and “Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies” is in the British Museum. The last one was stolen by a British officer during the occupation of Beijing by the Eight-Nation Alliance and the looting of the Old Summer Palace (Yuanmingyuan). He returned to London intending to sell the jade fittings on the scroll to the British Museum. However, the museum recognized its value and purchased the entire scroll for 25 pounds at the time.

Interestingly, Qianlong’s favorite painting wasn’t “Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies,” but rather Huang Gongwang’s (黄公望) “Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains” (《富春山居图》). He was so fond of this painting that he took it with him on his southern and eastern tours to Inner Mongolia for hunting and the summer resort. Qianlong wrote a total of 55 inscriptions on the painting, filling up all the blank spaces. However, humorously, the version he inscribed on was a fake, known as “Shanju Tu” (《山居图》). The real “Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains” was also in Qianlong’s possession, in a scroll known as the Ziming Scroll (子铭卷), which he acquired in the 10th year of his reign. The following year, in the 11th year of his reign, Qianlong acquired the genuine “Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains,” known as the Wuyongshi Scroll (无用师卷). Wuyongshi was the monastic name of Zheng Shu (郑樗), a Taoist priest and the younger brother of Huang Gongwang.

Who delivered the authentic “Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains” to Qianlong?

It was Fuheng (傅恒), the chief minister of the Grand Council and brother of Qianlong’s first empress, Empress Xiaoxianchun (孝贤皇后) of the Fuca (富察) clan. Qianlong paid 2,000 taels of silver for this genuine painting. The money was given to the collector, as Fuheng dared not ask the emperor for money.

Empress Xiaoxianchun / Image Source: Wikipedia

However, Qianlong mistakenly believed that the Wuyongshi Scroll was fake. For years, people mocked Qianlong, claiming he lacked the ability to distinguish genuine works of art. When he first acquired the Wuyongshi Scroll, Qianlong instinctively felt it was real, but he deferred to the collective opinion of his ministers, who all agreed that the “Shanju Tu” was genuine, leading Qianlong to accept the forgery as real.

He even wrote a self-critique on the “Shanju Tu” and stamped it with five seals: “Qianlong’s Appreciation” (乾隆鉴赏), “Treasure Viewed by Qianlong” (乾隆御览之宝), “Stone Canal Pavilion” (石渠宝笈), “Three Rarities Hall” (三希堂精鉴玺), and “For Posterity” (宜子孙).

The real “Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains,” on the other hand, was only stamped with one seal, “Treasure Viewed by Qianlong,” as it was considered of secondary importance. The fake “Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains” is now housed in the National Palace Museum in Taipei, while the genuine “Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains” is also in Taipei, but another part, known as the “Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains (The Remaining Mountain Scroll)” (《剩山图》), is in the Zhejiang Provincial Museum. The Taipei version is longer and more complete, but bears burn marks and has been restored. This is the portion that Qianlong saw. The “Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains (The Remaining Mountain Scroll)” in Zhejiang is shorter but intact. It has never entered the Forbidden City and has always been circulated among private collectors.

The “Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains” was not stored in “Si Meiju” but in the Huachanshi (画禅室) in the rear hall of the Palace of Universal Happiness, where many famous paintings were kept. Qianlong’s favorite Chinese painter was Jin Tingbiao (金廷标) from Huzhou, Zhejiang. When Qianlong made his second southern tour, Jin Tingbiao presented him with the “Portrait of the Twelve Lohans” (《十二罗汉图》), after which he was brought to Beijing and became a court painter in the Forbidden City. Qianlong even broke tradition and granted him the rank of seventh-grade official.

Another notable painter was Giuseppe Castiglione (郎世宁), an Italian who Qianlong posthumously granted the rank of third-grade official. Castiglione came to Beijing at the age of 27 and worked in the palace for 51 years. One of his main tasks at the court was painting portraits of the imperial family, a skill he excelled in. Although no portraits from the Kangxi era have survived, his earliest known work dates back to the second year of Yongzheng’s reign.

In the first year of Qianlong’s reign, Castiglione painted a family portrait of Qianlong with his 12 consorts, which is now held in the United States. Western painting techniques, with their sense of depth and anatomical accuracy, appealed to Chinese tastes. However, to conform to palace customs, shadows were not allowed in portraits, yet Castiglione’s work still managed to convey a strong sense of depth and texture. Qianlong is the emperor with the most portraits in history, and Castiglione contributed significantly to this.

From 9 PM to 11 PM, it was time for the emperor to read. The emperors of the Qing Dynasty were all avid readers. Among the ten Qing emperors who ruled after the dynasty established control over China, only Emperor Tongzhi was not known for his scholarly pursuits; the others were all dedicated and capable readers.

Emperors Kangxi and Qianlong were especially studious, with Kangxi reading to the point of exhaustion and even spitting blood. The Forbidden City had many study rooms. Just within the Hall of Mental Cultivation, the emperor had several reading rooms.

One of Qianlong’s favorite small studies was “The Hall of Three Rarities” (三希堂). This room was half kang (a heated brick bed) and half floor, with a throne on the kang. The room was originally called “Wenshi” (温室), and its small size made it easier to keep warm. When the emperor read, he was not accompanied by palace maids offering perfumed sleeves; instead, he was surrounded by eunuchs. Only the empress dowager, empress, and concubines had palace maids by their side. The first formal study in the Forbidden City was the Study Room of the Palace of Heavenly Purity(乾清宫书房), established by Emperor Shunzhi as the first official study room in the imperial palace.

Emperor Qianlong had a saying: “I’ve been reading in the palace since I was a child for over 20 years; I am essentially a scholar.” He believed that without a solid education, one was not fit to be a gentleman. Why did he label himself a “scholar,” and why did he emphasize the importance of scholarly qualities? Because outside officials, like governors and provincial inspectors, often demeaned their subordinates in their memorials and reports, saying things like, “Scholars are not fit for the job” or “Bookish fools are useless.” This attitude did not align with Qianlong’s values as a scholarly emperor, so he proudly labeled himself a “scholar” to challenge these criticisms. He emphasized that without scholarly qualities, one couldn’t hope to stay in his good graces.

Reading was something the emperor enjoyed for its own sake, a solitary activity where he could lose himself. But sometimes, the emperor also enjoyed reading with others. In the Forbidden City, there were two places for this: Maoqindian (懋勤殿) and Nanshufang (南书房). These were places where the emperor could engage with others in literary pursuits. The officials assigned to these places were not permanent positions but temporary assignments, yet they were considered a great honor. Why? Being granted the title of “Nanshufang Attendant” (南书房行走) meant that you could freely enter Nanshufang and accompany the emperor in appreciating books and paintings, discussing literary insights. Only the most distinguished scholars from the Hanlin Academy (翰林院) could be assigned here, and in a sense, they became imperial tutors.

The emperor enjoyed studying and reading at night. He didn’t just read books; he also wrote them. Each emperor had their own collected writings and decrees. For example, Emperor Shunzhi wrote a particularly touching piece in memory of Consort Donggo (董鄂妃), expressing his grief and desire to become a monk after her death. Emperors Kangxi and Qianlong both loved writing poetry. Qianlong, in particular, was the most prolific poet in history, with 42,000 of his handwritten poems still preserved in the Forbidden City. Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong all habitually stayed up late.

Did the emperor bathe before going to bed? Yes, he did. While it’s uncertain whether the emperor bathed every day, he was certainly the person who bathed the most in the Forbidden City, even more than the concubines in the harem. This was partly due to the various official ceremonies that required the emperor to purify himself through bathing before offering prayers to the heavens and various deities. Although the palace had no dedicated bathroom, the emperor bathed in a tub made of wicker coated with multiple layers of lacquer. The outermost layer was reddish-brown with gold-painted floral designs.

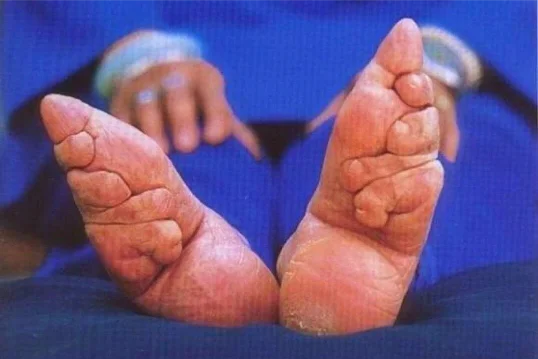

Flip The Plaques

Now, we come to the final part, which might be the information and details that some readers are most curious about. Before going to bed, the emperor would also “flip the plaques.”

To make it easier for the emperor to choose a consort, the Jingshifang – office for administering eunuchs(敬事房), a department under the Imperial Household Department, would create bamboo plaques about a foot long and an inch wide, based on the rank and surname of the concubines. Because the top part of these plaques was painted green, they were called “Green-headed Plaques” (绿头牌).

Jingshifang was originally responsible for managing the eunuchs and palace maids, but by the Qing Dynasty, it also took on the task of overseeing the emperor’s intimate affairs with the empress and concubines. After the plaques were made, the chief eunuch would first take them to the empress for her review. Only with the empress’s approval and her seal could these concubines be added to the list of candidates for the emperor’s bed-chamber. After the emperor had finished his evening meal, the chief eunuch would carefully select a few of the plaques, place them on a silver tray, and present them to the emperor for him to choose. If the emperor was not in the mood, he could simply say, “You may leave,” and the eunuch would take the tray away.

Many people imagine that with the emperor surrounded by so many concubines, he would indulge himself every night. This might have been common in other dynasties, but Qing emperors were known for their diligence. They would rise before dawn to handle state affairs, working for more than 10 hours a day. By evening, their energy was often nearly exhausted, and engaging in frequent physical activity with the concubines could be too much to handle.

If the emperor was in good spirits and wanted to summon a concubine, he would select a Green-headed plaque and flip it over, which was called “flipping the plaque” (翻牌子). The concubine whose plaque was flipped would be the lucky one to spend the night (not the entire night) with the emperor. Once the selection was made, the chief eunuch would immediately notify the Tuofei eunuch – Concubine-Carrying Eunuch (驼妃太监), (“Tuo” means carry something or someone on his back, “Fei” means “concubine”), who would go to the chosen concubine’s residence and inform her to prepare by bathing.

Once everything was ready, the Concubine-Carrying Eunuch would wrap the freshly bathed and undressed concubine in layers of red silk, then carry her, like a “spring roll,” to the emperor’s residence. Upon reaching the second door of the emperor’s chamber, the concubine would emerge from the red silk, change into a silk robe, and be delivered to the emperor’s bed. You might think that the fun begins here, but not so fast. According to “Qing Dynasty Anecdotes” (《清代野记》), there was another step: “The emperor would lie down first, leaving the lower part of the blanket open, and the concubine would crawl up naked from the foot of the bed into the emperor’s embrace.” In other words, after reaching the bed, the concubine would have to crawl, naked, from the emperor’s feet into the bed before anything could start.

At this point, the chief eunuch and the Concubine-Carrying Eunuch would discreetly leave and wait outside the door. Their purpose wasn’t to protect the emperor’s privacy but to… keep track of time.

According to palace regulations, the concubine’s time in the emperor’s bed was limited to half an hour. When the time was up, the eunuch would call out from the door, “Time’s up!” This could be quite a mood killer. If the emperor was still engaged, he might pretend not to hear and continue. However, the eunuchs, holding the “Ancestral Command” (祖宗令箭), would courteously call out three more times from the door. If the emperor still showed no sign of stopping, the eunuchs would have no choice but to enter, pull the concubine out from the emperor’s bed, rewrap her, and carry her back to her quarters.

After the concubine was returned to her quarters, the eunuchs of Jingshifang – office for administering eunuchs had another task to perform: they would ask the emperor, “Should he stay?” If the emperor agreed to let the concubine bear his child, the eunuchs would carefully record the details of the concubine’s menstrual cycle, the time of the night, and the specifics of the encounter in case a pregnancy needed to be confirmed later. If the emperor did not want to leave a descendant, the eunuchs would take special “contraceptive” measures “by pressing on the concubine’s lower abdomen, causing the imperial semen to flow out.”

After this, the emperor and the concubine could each sleep peacefully without disturbing each other. Under such bizarre regulations and with such a short amount of time, the emperor’s intimate encounters with his concubines were purely for the purpose of continuing the imperial lineage. There was no foreplay, no aftercare, and no semblance of normal marital relations.

However, there was one exception to this system: the empress. Only the empress was allowed to spend the entire night with the emperor. This privilege alone was enough to make the concubines, who had to carefully maneuver for half an hour of the emperor’s attention, envious. When the emperor spent the night with other concubines, it was called “shiqin – serve the emperor in bed” (侍寝), but with the empress, it was called “banqin” (伴寝), which means “companionship in bed.” The difference in terminology reflected the vast difference in treatment. Besides having no time restrictions, the “Qing Dynasty Veritable Records” (《清实录》) clearly stated that on the first and fifteenth day of each month, the empress was required to sleep with the emperor. No matter how busy he was, on these two days, the emperor had to share the bed with the empress.

Moreover, the procedure for the empress’s companionship was much simpler. There was no need for the Concubine-Carrying Eunuch, no need to be wrapped like a “spring roll,” and no need to worry about whether to leave a descendant. The emperor would simply visit the empress’s palace in person and enjoy their exclusive “wonderful time” together. During this time, the eunuchs of Jingshifang – the office for administering eunuchs would carefully record the dates and times the emperor and empress shared a bed to verify any future pregnancies.

Before the emperor flipped the plaques, they had to be reviewed by the empress. The empress decided who could serve the emperor that night, and only those she approved would have their plaques presented to the emperor by the chief eunuch. If a concubine did not follow the rules, the empress had the authority to reprimand her, and the emperor could not interfere. Some might wonder if the Qing emperors didn’t have the empress to accompany them through the night.

Unfortunately, most Qing emperors and empresses had politically arranged marriages. They neither liked their empresses nor enjoyed spending the night with them. For example, the “Qing Dynasty Veritable Records” stated that after the emperor and empress were married, they had to live together for a full month before returning to their respective residences. However, only Emperor Kangxi managed to follow this rule among the twelve Qing emperors.

Emperor Guangxu, on his wedding night, cried uncontrollably in the arms of Empress Longyu, his cousin, whom he found dull and uninteresting. He moved out after just six days.

In the long and often cold relationships between emperors and empresses, the empress often became little more than an elegant ornament. Besides the personal dislike of the empress, another reason that led to the estrangement between emperor and empress was their dedication to state affairs. The emperors of the Qing Dynasty were known for being among the most diligent rulers in history, with the highest overall competence.

Among them, Emperor Yongzheng was undoubtedly the most representative. His diligence was well-known. He worked almost every day of the year except for his birthday, New Year’s Day, and the Winter Solstice. Although the palace regulations required the emperor to go to bed at 8 PM, Yongzheng almost never adhered to this rule, often working late into the night. Historical records show that Yongzheng slept only four hours a night. To ensure a clean government and smooth communication between the central and local governments, Yongzheng reformed the secret memorial system, allowing officials above the third rank to write directly to the emperor. At its peak, this group included more than 1,200 officials. Yongzheng was extremely meticulous in reviewing these memorials. If he found any errors, he would correct them personally. It is estimated that Yongzheng wrote at least 10,000 characters a day, and over the 13 years of his reign, he wrote at least 10 million characters.

What’s even more remarkable is that Yongzheng exercised great restraint in matters of romance. The woman he loved most in his life was Imperial Noble Consort Dunsu (敦肃皇贵妃年氏). From the time she married into the Yinzhen Prince’s Mansion in 1712 until her death in 1725, a period of 11 years, Yongzheng did not have children with any other woman. All four of his children born during that time were from Imperial Noble Consort Dunsu. In the ten years following her death, Yongzheng fathered only one more child, with Consort Qian (谦嫔).

Among the twelve Qing emperors, there were not only “ascetic” types like Yongzheng but also “indulgent” ones like Emperor Tongzhi. However, even with the restrictions of the bed chamber system, Tongzhi, despite having access to many concubines, could not fully indulge in his desires. As a result, the young and passionate Tongzhi would secretly sneak out of the palace to visit the brothels in Beijing’s Eight Great Lanes (八大胡同), sometimes not returning until the next morning. Unfortunately, Tongzhi contracted a venereal disease (some say smallpox) and died at the young age of 19.

Emperor Tongzhi / Image Source: Wikipedia

This shows that even as the “ruler of all under heaven,” the emperor was not truly free. To be a good emperor, one had to handle mountains of state affairs every day. And as for taking it easy? That was simply unrealistic. Even in the seemingly trivial matter of choosing a concubine for the night, the emperor was bound by ancestral rules and closely monitored by eunuchs, leaving little room for personal freedom.

That’s it! Thank you for your patience in reading.